Talking with migrant labourers and field workers in Chiang Mai about COVID-19 test measures.

Following a December 2020 outbreak of Covid 19 among migrant workers in Mahachai, Samut Sakhon, foreign workers around Thailand, a group with comparatively high infection rates, were targeted by the government for pandemic control measures. Under the new policy, those who refused testing were not allowed to register for work. They were also denied work permit and visa extensions. Migrant workers who agreed to take the test were forced to pay expensive fees in advance, adding another worry to their lives.

On 29 December 2020, the Thai government issued a cabinet resolution to implement Covid-19 control measures for migrant workers in Thailand. Because of the pandemic, Cambodian, Lao, and Burmese nationals illegally working in the country were going to be allowed to register online for work and could remain in Thailand until 13 February 2023. The plan was to let state authorities get a better idea of how many migrant workers were in Thailand, making it easier to control the spread of Covid.

The policy posed new problems for migrant workers, however.

A 2020 ministerial regulation prohibiting individuals with leprosy, tuberculosis, syphilis and addiction problems from entering Thailand was revised to include Covid-19. Those coming to work in the kingdom were required to undergo testing. Illegal workers hoping to register online and remain in country under the new policy did too, as did legal workers renewing their documents. So did their local dependents.

The test fee was set at 3,000 baht and anyone wanting to stay in country had to pay. Without the test, they could not extend their visas. Without it, they could not renew their work permits. Without it, they would not be allowed to formally register.

Added to the fees already assessed for work permit extension, health checks, insurance, registration and the issuing of pink card IDs, each worker suddenly needed to pay as much as 9,180 baht. If they had children, the amount was even higher. The rates for dependents varied by age from 3,800 – 7,300 baht. The mandatory 3,000 baht Covid test fee applied to them as well. It was and remains an exceptionally heavy burden for migrant workers, many of whom have been unemployed since the pandemic began. Many families have been left without work and income.

Collecting exorbitant COVID-19 test fees in advance: how has the policy affected the lives of migrant workers?

According to the law, the revised regulation on prohibited diseases should not have come into effect until 25 Jan 2021, 30 days after being published in the Royal Gazette.

Despite this, however, a large number of migrant workers in the Chiang Mai region were called in to take mandatory 3,000 baht Covid tests at state hospitals before that date by Immigration Bureau authorities. Migrants hoping to register and workers needing to extend their documents before the end of March were the most affected. Having heard that they were going to be charged 3,000 baht for COVID-19 tests from 25 Jan, many workers hurried to extend their visa and work permits – not to avoid getting tested for COVID-19, but because they had not prepared their hearts or money for the suddenly increase in fees.

The pandemic has resulted in massive unemployment around Thailand. Migrant workers have also suffered - many no longer have work. Those going to the Immigration Office before 25 January were chased away to get tested for COVID-19 nonetheless.

According to Jai (alias), a Shan migrant worker:

“When I went to immigration to extend my visa, they said I needed to have COVID-19 medical certificate, that if I didn’t, I couldn’t extend. I didn’t have it so I was planning to come back … but my broker said I didn’t need to test, that if I paid 3,500 baht they would extend my visa. I gave in and paid the 3,500.”

She agreed because this amount included her visa and work permit extension fees. If she had gone to get tested instead, she would have need pay a total of 5,000 baht - 1,900 baht for visa and work permit extension, 3,000 baht for a COVID-19 test, and a processing fee of 100 baht.

Given how difficult it is to earn money at present, the deal seemed reasonable, and not just to Jai but to others. She quickly added: “Everyone’s trying to avoid the 3,000 baht test now … we are all running to our brokers instead.” Where their medical certificates came from is an open question.

“I don’t know where they get the COVID-19 test results from. Maybe they don’t need them because they have some sort of understanding. That’s their affair. We have no way to know anyway… we just give them our passports. I don’t know how they work together with Immigration. They just return when the visa is ready,” Jai said.

Min (alias), a woman worker with the Migrant Working Group, a labor support network in Chiang Mai, added that the worker community had its own marginalised elements who had no way to manage their visa extensions and 3,000 baht COVID-19 tests.

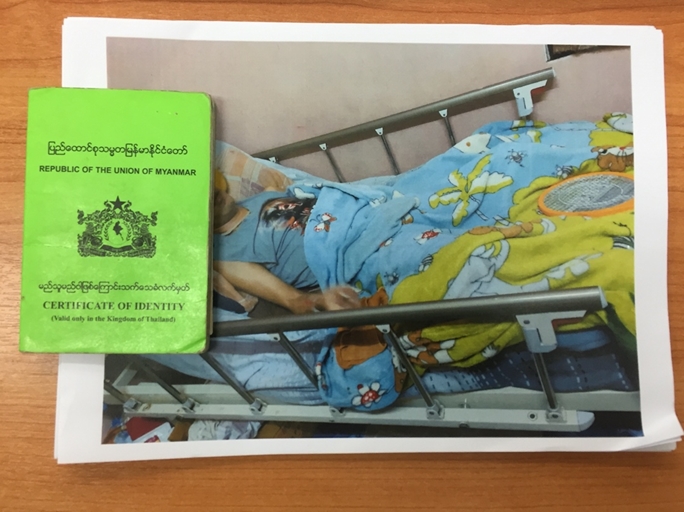

“There is this person bedridden from a car accident. He has no money to pay a broker. His wife is not working either and they have 2 children. He can’t extend his visa because he needs to get a COVID-19 test at the hospital and he doesn’t have any money,” she explained.

Some migrant workers have had to borrow money from loan sharks in order to pay extension fees. “We found one family of 4, all migrant workers, who had to pay the broker almost 20,000 baht. They had no money so they had to borrow from a local money lender.” Jai, who had the experience of borrowing money to extend her visa and work permit last year, grumbled, “I haven’t even paid off the old one yet, and it’s already time to get a new one.”

Jai was a maid in the home of her Chinese employer. He was in China when the Covid outbreak began and was unable to return to Thailand. She lost contact with him and her work permit eventually expired. In March of 2020, the government announced that foreigners in Thailand could remain until 30 July 2020 without reporting to the authorities every 90 days. This allowed her to stay in country without extending her visa. In the end, however, immigration authorities told her that as she no longer had a work permit, she would be sent home. That is when Jai hurriedly ran to a broker.

She can’t go back to Myanmar.

Jai’s husband is Thai. She also has a child here. In this respect, she is no different from many other migrant workers living in Thailand. Some are married to Thai citizens, some were born here and can only speak Thai and Shan, not Burmese. They don’t know how they would live in Myanmar. Their family and life are here.

The broker told Jai to find a new employer.

“I was like, oh no! My previous employer never came back to sign off on me. What could I do? In the end, I had to hire another Thai person to act as my employer. I found one who agreed to do it for 1,000 baht. When I told the broker, he said I had to pay another 2,000 baht to deal with the name difference. In total, they charged me 12,000 baht. I paid. I didn’t have a card anymore and was scared of getting sent back.”

Then, when they took my old passport to Immigration, they came back and said I didn’t report in. Even though my visa was expired, I was supposed to report in every 90 days. Because of this, there was a fine of 1,200 baht. Even though my visa expired during the pandemic, even though I was allowed to remain in country, they said I was supposed to report in.”

In the end, for the right to spend a year working legally in Thailand, Jai paid 13,200 baht - a debt she has yet to begin repaying. And now, the time for annual card extension has arrived again. During the pandemic, the work permits of many workers were not used; they lived here but had no work to do.

James (Sai Tip Awan), officer at Human Rights and Development Foundation, Chiang Mai

“James” Sai Tip Awan, who works with the Human Rights and Development Foundation in Chiang Mai, helped us to better understand immigration policy and the different measures used to control foreign nationals and migrant workers in Thailand during the pandemic. According to James, immigration policies varied by visa type. James holds a Non-O visa - unlike the Non-LA visas issued to Cambodian, Lao and Burmese migrant workers.

“When the pandemic hit, the government announced that foreigners could stay on without a visa. They didn’t need to report in. I didn’t need to report every 90 days. The government said that we could stay until 30 July 2020. For 4 months I didn’t worry about the 90-day report. I was 20 days late when I went to immigration and they didn’t say anything. Those of us with expired Non-O or Non-B visas didn’t need to extend. But for migrant workers, miss a report and you were fined”.

The reporting processes also differed. James could complete the process in five minutes from his car, parking beside immigration and handing officials a single document - his passport.

Migrant labourers using brokers could also complete the process with only their passports but if they went to immigration themselves, they had to queue up early in the morning with copies of their employer documents, passports and work permits.

When James extended his visa, his foundation prepared all the necessary documents for him to submit. When labourers use documents given to them by their employers, immigration officials sometimes demand that the employer come in person. Blood and health tests for holders of Non-O visas can be done anywhere. In private hospitals, it takes twenty minutes and 200 baht. Migrant workers are required to go to state hospitals, pay 500 baht and spend a day waiting.

“It seems to me that government policy makers treat workers as if they were a problem, a group that needs to be tightly regulated and forced to obey. And to stay here, migrant workers have to pay two to three times what tourists and foreign nationals holding Non-O or Non-B visas do.

People with Non-O and Non-B visas - people who work in foundations, as interpreters, or as university lecturers - pay a visa fee of 1,900 baht per year and are not forced to take blood tests at state hospitals to get work permits as stipulated by the Ministry of Labour. In the case of migrant workers, the list of prohibited diseases is the same… but their lives are made more difficult by all of extra steps to extend their visa and work permit. That is why they rely on brokers - they don’t need to speak much, just give them the documents and it’s done,” James said.

Covid test fees and labour activist concerns

A number of people working on labour issues have expressed concern about the classification of Covid-19 as a prohibited disease and the imposition of a 3,000 baht COVID-19 test fee.

Pasuta Chuenkhachon, officer at the Human Rights and Development Foundation

As noted by Pasuta Chuenkhachon, an officer at the Human Rights and Development Foundation, “after COVID-19 was listed as a prohibited disease, workers who became infected could be sent home, not because they lacked the necessary skills to be here but rather because they had contracted a prohibited disease. If they are sent back when border stations are closed, where will they go? And what happens to their families here?”

Sukanchata Sukphaita, officer at the Human Rights and Development Foundation

Another officer at the Human Rights and Development Foundation, Sukanchata Sukphaita, posed the question of why migrant workers needed to pay a 3,000 baht test fee when much cheaper tests could be done by the Ministry of Public Health.

“The Ministry of Public Health has three types of COVID-19 test. The first, a test to see if someone is COVID negative or positive, costs 1,000 baht. More detailed results can be obtained with tests costing 2,000 and 3,000 baht. Why not first test workers to see if they are negative or positive? Instead, state hospitals administered the detailed test at 3,000 baht right away, even before the new law came into effect.

“And now that the new law has been gazetted, will it ever be taken out? If the pandemic ends, will the workers still need to take the tests? And what happened to Social Security and health insurance? Why don’t they reach out to help? They took workers’ money so why not take responsibility for their health now? Whenever a new disease emerges, migrant workers always seem to be charged more and more.”

“It is interesting to note that the Thai government once established a ‘return fund’ for migrant workers. They collected money from migrants - 2,000 baht per person - when they registered for a year. Later, when workers were returning home and asked for their money back, border immigration officials refused, saying it would be paid by the original employment brokers. Responsibility was thrown back and forth and in the end, workers never got their money. Instead, the government stopped collecting it and transferred what they had into an ‘alien management fund’. This was estimated to have had about 2 billion baht, calculated by the million or so migrant workers who entered Thailand the year the money was collected.

“The fund truly belongs to migrant workers. It does not come from taxes on Thai citizens and it has enough money to support workers in times of need - like now.”

To stop the risk of migrants spreading Covid, she suggests that the money be used to check for COVID-19, using the cheapest method possible to see who is negative and positive. She added that otherwise people would continue to find ways around the system and the number of tested workers would fall …. “and if this happens who can we blame but ourselves? The current policy goes against reality.”

Since the pandemic began, migrant labourers have received little support from the Thai government. To the contrary, as the pandemic deepened, their lives have been made tougher by old government policies and new ones alike. With the deteriorating economy, exorbitant test fees are beyond the reach of many workers. The policy should be immediately revised. The implementation of such unrealistic policies will not only have an impact upon the number of registered migrant workers in country, forcing people to live in the shadows, it will also make the control of COVID-19 here more difficult.

References:

[1] Royal Gazette “Ministry of Interior announcement on allowing certain groups of aliens to stay in the Kingdom as special cases, under the spread of the corona virus 2021, according to the Council of Ministers resolution on 29 December 2020,” source: http://www.ratchakitcha.soc.go.th/DATA/PDF/2563/E/305/T_0012.PDF

[2] Royal Gazette, “2020 Ministerial Regulation on prohibited diseases for aliens entering the Kingdom or those entering for residency within the Kingdom.” http://www.ratchakitcha.soc.go.th/DATA/PDF/2563/A/105/T_0012.PDF

First published on 18 January 2021 at https://prachatai.com/journal/2021/01/91254

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”