A newly-launched book documents the ongoing case of Somsak Chuenchit and his 12-year effort to bring the police officers who tortured his son by beating and suffocating him with plastic bags during an interrogation.

From left to right: Ritthirong and Somsak Chuenchit. (Source: Cross Cultural Foundation)

On 28 January 2009, Ritthirong 'Shop' Chuenchit ,18, was returning from a cinema in Prachinburi Province with a friend when he was stopped by the police. His clothing and motorcycle helmet reportedly fit the description given to police by a woman who had earlier been the victim of a gold necklace-snatching.

At the police station, the woman identified Ritthirong as the person who had taken her necklace. Ignoring his assertion of innocence, the interrogating officers beat the handcuffed youth and then suffocated him in a bid to determine where the necklace was hidden. Whenever Ritthirong chewed holes in the plastic bags to breathe, more were placed over his head.

The interrogators also told Ritthirong that if he died, they would hide his corpse in a far-away wilderness. Terrorised, the youth decided that the only way to escape was to admit to the theft and claim that the necklace was at a shop he frequented.

After beating him some more, the police accused him of being on drugs and sought evidence with a urine test, which later proved to be negative.

Eventually, Ritthirong ’s father Somsak arrived on the scene, launching a fight to restore his son’s dignity.

Rough road for justice

Torture at the hands of the police left the 18-year-old student and acoustic guitar player with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and he has since required ongoing medical treatment. He is often awakened by nightmares and his appetite for guitar playing and music has declined.

In a bid to get justice for his son, Somsak filed a complaint about the assault. The perpetrators worked to stop him, lobbying him to drop the case, fabricating evidence, and harassing him with the threat of drug charges. Police officers also appeared at Ritthirong’s school, exacerbating the concerns of an already-frightened student.

A rally poster against torture and enforced disappearance. (File photo)

“I had to fight alone. I had to fight the police. Some units, some police violated our rights by violating and depriving my son of the right to breathe. Even the air to breathe they wouldn't give him,”

"I haven't been mixed up with drugs at all. But in 2011 I was told by a local government agency to go for drug rehabilitation. I took this letter to the District Chief telling him that I had no history with drugs. This was the beginning of the threats,” said Somsak.

Somsak's case began to draw public attention after he contacted Amnesty International and the Cross Cultural Foundation (CrCF), a rights advocacy group. With the aid of a CrCF legal team, Somsak filed a lawsuit in 2015 against the 7 police officers involved in the incident for malfeasance, perverting the course of justice, assault and illegal detention .

Far from over

Thus far, Somsak’s efforts have borne little fruit. After 12 years of struggle, only one police officer has been punished. Sentenced to prison for 16 months and fined 8,000 baht fine for interfering with an investigation, he has already been paroled.

Somsak is still pursuing cases against the police for utilising false testimony and fabricated evidence to frame his son. Police are pursuing a case against him in turn for allegedly presenting false information in court.

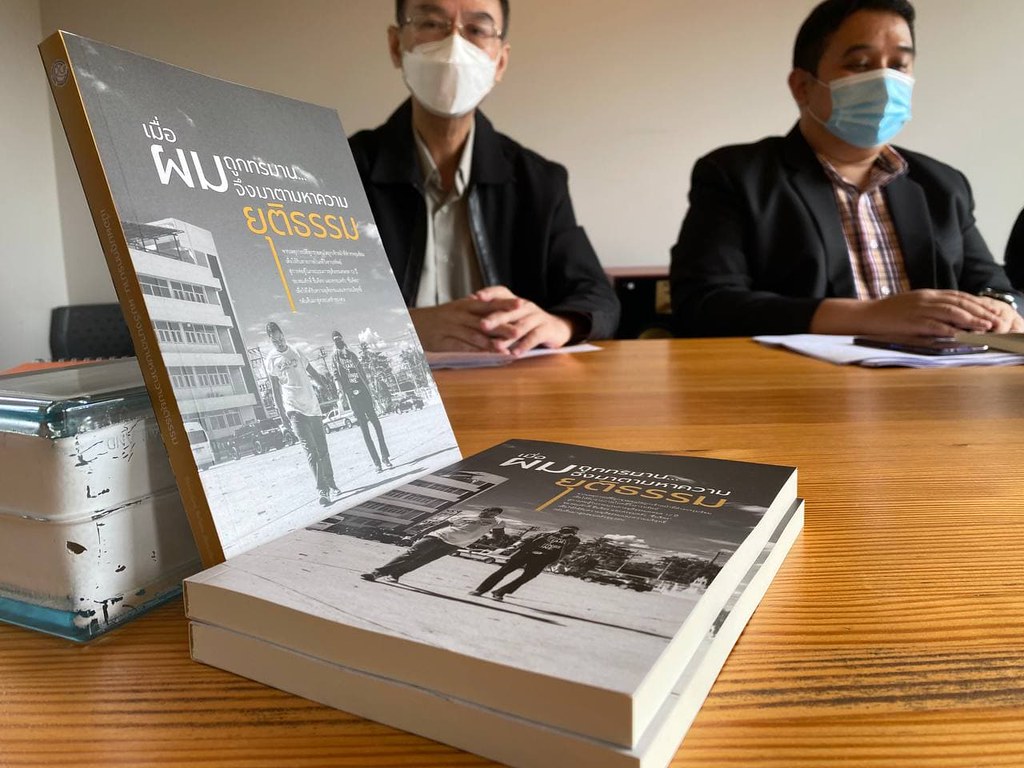

Aitarnik Chitwiset, the author of When tortured, I sought justice, spent over 6 months collecting data and conducting interviews before writing a book about the case. He believes that Somsak's struggle is worth keeping an eye on. On a number of occasions, patron-client networks in the bureaucracy were used to block Somsak's efforts, reflecting a fundamental defect in a state system that needs reform.

When tortured, I sought justice at the book launch event on 10 September 2021.

Preeda Nakpiw, the CrCF lawyer in charge of Somsak's lawsuit, blames the lack of a law criminalising torture, which makes it relatively easy for wrong-doers to escape punishment. An anti-torture and enforced disappearance bill will ensure that mechanisms are in place to end such practices.

Civil groups and the relatives of victims are working to assure that it is adopted. Delayed for seven years, a first reading of the bill finally passed parliament on 16 September with a 363-0 vote. A second and third reading remain however.

According to Surapong Kongchantuek, the president of CrCF, torture and enforced disappearances are often carried out in places with limited public access, such as military barracks, police stations or national parks, making it difficult to gather evidence and investigate culprits.

Eventually, the parliament has passed the first reading of the bill on 16 September with an overwhelming 363-0 vote. Howver, the actual enforcement is still far as further debates over the details are needed before passing the second and third reading.

According to Surapong Kongchantuek, the president of CrCF, torture and enforced disappearances are often carried out in places with limited public access, such as military barracks, police stations or national parks, making it difficult to gather evidence and investigate culprits.

He believes the passage of the anti-torture bill will create a legal toolset to pursue investigations. He also proposes police reforms to decentralise the command structure, facilitate independent investigations, enforce rules of conduct for interrogations including the mandatory use of voice and video recorders, provide clear criteria for internal promotions and eliminate the current “bounty system” which encourages unwarranted police raids and abductions.

As for Somsak and his protracted struggle for justice, he wants his family to be remembered for their stand against abusive authorities.

“We have been branded as scapegoats. We refuse to be sacrificed. So we must look for every way to fight. This is a fight not to be scapegoats.”

This article uses material from Aitarnik Chitwiset’s new book “When tortured, I sought justice” published by the CrCF and information given at the book launching. If you are interested in obtaining a copy, click here. The book is in Thai language)

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”