Note: On May 24, 2016, the junta government announced that it will submit Torture and Enforced Disappearance Prevention and Suppression bill to the military-appointed National Legislative Assembly. It also said Thailand will ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. The following story has been published since January 2015.

Eight years after Thailand signed the UN conventions against torture and enforced disappearance, the Justice Ministry plans to submit a bill against torture and enforced disappearance early in the year. The bill is praised by activists working in the field for including all elements possible from international laws. The bill, if passed, will be the first law to recognize and criminalize torture by the Thai authorities. It will also recognize and criminalize enforced disappearance, even without the body of the victim. However, under the military junta, which itself has allegedly resorted to both means to suppress dissent, one must be very sceptical. (See report of torture and enforced disappearance allegation against /under the junta

1,

2,

3,

4)

Throughout Thai history, state officials have perpetrated torture and enforced disappearance and never been punished. Part of the reason is the lack of any law which criminalizes torture and enforced disappearance. In fact, some officers who committed these crimes were promoted while civilians who spoke out were punished.

In 2014, the Army filed a libel suit against

Pornpen Khongkachonkiet, a human rights lawyer and Director of the Cross Cultural Foundation (CrCF) of Thailand. Pornpen is accused of causing damage to the reputation of the Army by submitting a report to the UN about alleged torture committed by the Army. In 2011, Suderueman Maleh was sentenced to two years in jail for reporting torture allegedly inflicted upon him by police. The lawyer representing Suderueman in this torture case was abducted and disappeared ten years ago. Yes, that lawyer was the prominent Muslim lawyer Somchai Neelapaijit.

“The reason why torture continues is that the perpetrators continue to get away with it. When one police officer or soldier carries out torture and is not held to account (because there are no legal or political structures to do so), his colleagues learn that they too can do so. Impunity is pedagogical,” said Tyrell Haberkorn, an expert on violence and human rights violations in Thailand from the Australian National University.

Torture and enforced disappearance flourish when there is an agenda or policy to crack down on certain groups of people, such as “Communists,” "hooligans," "terrorists," "drug traffickers," said Haberkorn.

Moreover, most victims belong to ethnic minorities or the marginalized on the border where the rule of law is weakly enforced..

The special security laws, such as martial law and the Emergency Decree, even create loopholes for the authorities to commit such crimes. These laws allow the authorities to arrest and detain people without warrants. Martial law allows the authorities to hold detainees at unknown, undeclared places and detainees are usually not allowed to contact anyone. In the restive Deep South, where both laws are imposed, insurgent suspects are usually detained up to 37 days without charge. Surveys found that most cases of torture in the Deep South are committed during the first few days of the detention under martial law.

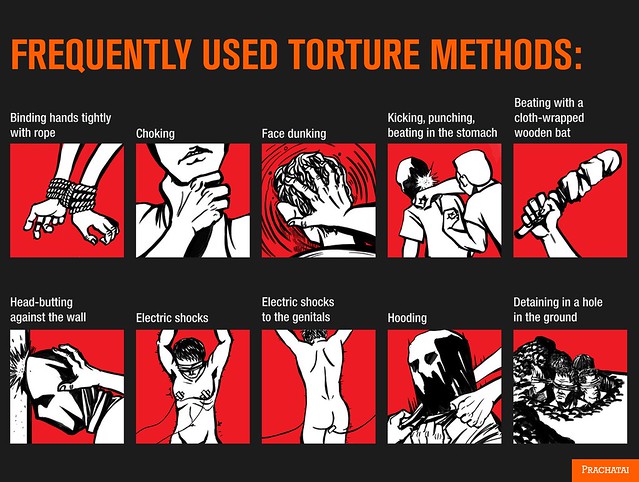

Officials often use the following torture methods to extract confessions: binding hands tightly with rope, choking, face dunking, kicking, punching, beating in the stomach, beating with a cloth-wrapped wooden bat, head-butting against the wall, and electric shocks. Some methods do not leave a mark: hooding, exposure to extremely high or low temperatures or light to darkness for extended periods of time, death threats, threats to harm detainees' family members, forced feeding or injecting drugs which lead to loss of consciousness

The ultimate cause of the two ongoing crimes, however, is the lack of respect of human dignity and human rights on the part of state officials, experts said. The Thai authorities never admit that they are involved in such activities. The Thai police reportedly, however, believe that torture is an effective method of crime control.

Currently, Thai law does not recognize nor criminalize enforced disappearance and torture. The current judicial process and apparatus themselves have caused huge obstacles to bringing to justice perpetrators of these two extraordinary crimes, deeply involving the state authorities. Imagine if a person was tortured by a police officer. S/He would have to start the judicial process by filing complaint with the police themselves. In the violence-plagued restive Deep South of Thailand, where the majority are Muslim Malay, a local person who was tortured and dared to file a complaint would usually be tricked into signing a document not to pursue the case against the officers, or the police would refuse to take the case, or even worse, charges related to insurgency would be brought as retaliation, according to Anukul Awaeputeh, head of the Pattani branch of the Muslim Attorney Centre.

In case of enforced disappearance, even greater problems arise from the law itself.

Enforced disappearance usually involves abduction, torture and murder with the bodies of the victims hidden or destroyed. However, in most cases, there is only evidence of abduction.

In case of Somchai Neelapaijit, the most renowned victim of enforced disappearance in Thailand, the Department of Special Investigation (DSI) reportedly told his wife that they know that Somchai was abducted, tortured, killed, and burned to ashes. The ashes were then scattered in a river.

The Court of First Instance in 2006 found only one from five police defendants guilty of coercion, which is a relatively minor offence. Later in 2011, the Appeal Court acquitted all defendants due to weak evidence. The court also said that it could not be confirmed that Somchai had been murdered or injured. But how could one find evidence of injuries or murders from enforced disappearance victims in the first place?

Somchai Neelapaijit who was last seen on 12 March 2004

In the eight years since Thailand signed and ratified the International Convention Against Torture and signed the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, the Thai state has drafted several versions of the bill, with networks of victims and activists working on the issues, reflecting their thoughts in the process.

The Torture and Enforced Disappearance Prevention and Suppression bill, mainly drafted by Pokpong Srisanit, a law lecturer at Thammasat University, under the supervision of the Justice Ministry, will be submitted to the cabinet around February. If the cabinet gives the green light to the bill, it is likely to be passed by the rubber-stamp National Legislative Assembly (NLA). The bill still has to pass several rounds of review and the version that is ultimately enacted may differ gravely from the current bill.

The current bill comprises four sections: suppression, prevention, the committee on the suppression of the crimes, and prosecution.

On suppression, the bill criminalizes torture and enforced disappearance.

While the Criminal Code sets the maximum jail term for physical assault at two years and for abduction up to 3-5 years, the jail terms for torture are understandably much higher.

Article 4 stipulates that any government official or employee of the state who commits torture must serve a jail term of from five to 20 years. If the torture leads to serious injury, they may face 10-30 years in jail. If a person is tortured to death, the official will face life imprisonment and a fine of 600,000 to one million baht.

In Article 5, officials who commit enforced disappearance will face five to 20 years in jail. If the enforced disappearance leads to serious injury, the officials will face seven to thirty years, but if the act leads to the death of the victim, the officials will face life imprisonment.

The bill also states that any government official who is aware of torture but ignores it, and those who may not be government officials or employees but who commit enforced disappearance as supervised and ordered by government officials must serve similar jail terms as in Articles 4 and 5. It also indicates that any commander who has the knowledge of the act, but intentionally ignores it, will have to serve half of the penalty that his/her subordinates serve.

The bill also states that no matter what situation the country is in, this law must be enforced -- no exceptions.

The law also prevents what happens in the Guantanamo Bay detention camp by extending the jurisdiction of this bill to cover crimes committed outside Thailand.

The law prevents the use of testimony and evidence obtained during torture or enforced disappearance during the prosecution process, except in the trial of perpetrators.

The prescription of the case is 30 years.

On suppression, the section closes loopholes which usually lead to abuse during detention.

- Any detention by authorities must be in a place which is declared, officially certified and open for inspection.

- Persons detained have the right to notify their families, lawyers or any trusted persons of the circumstances of their detention. They have the right to be visited by families, lawyers and friends.

- The authorities must record names, times and dates, the name of the official who orders the detention and the physical condition of detainees before and after the period of detention.

- The families of detained persons have the right to demand that the authorities to divulge these records. If the authorities refuse to do so, the families can petition the courts and the courts can order the authorities to reveal this information.

- If it is believed that someone is being tortured, anyone can petition to the court and the court must hold an urgent hearing on whether the torture allegation is true.

- The court can also order an end to torture and the release of persons tortured, send victims to hospital and provide other remedial measures.

- The bill also prohibits the authorities from deporting any person from Thailand, if it is believed that this action may lead to that person being tortured or disappeared.

Because of the notoriety of the Thai authorities, especially the police, the third section of the bill creates a committee with powers over the investigation to ensure that the spirit of the law is followed.

The committee will be composed of 16 people, chaired by the Justice Minister. Four are human rights defenders and two are victims or former victims of torture and enforced disappearance. The rest are from related state agencies. Having the victims on the committee is a step that the rights groups working on the issues have strongly fought for, Pratubjit Neelapaijit, an expert on enforced disappearance and the daughter of the disappeared Muslim lawyer Somchai Neelapaijit, told Prachatai.

This was the compromise between law enforcers and the families of victims. While most victims and their families do not at all trust the police and the authorities to handle investigations and called for an independent agency to handle cases, the authorities say ordinary people are not trained to investigate crimes and are not equipped to do so.

The committee’s main responsibility is to oversee investigations into allegations of torture and enforced disappearance. However, investigations are still conducted by state authorities. Article 33 states that the committee must assign state authorities to investigate the case and must take into consideration conflict of interest and effectiveness.

This was designed to avoid scenarios where cases are handled by the police unit which has a stake in the case or is itself involved in the crimes.

Other tasks of the committee include petitioning the courts to start a hearing on torture allegations, designing remedial measures and policies for victims, and making proposals to the cabinet on improving policies and measures to prevent and suppress the two crimes.

Currently, such cases have a long fight to get to court. The victims must make a complaint to the police. The police then conduct an investigation, press charges and send the case to the prosecutor. The prosecutor then files the case with the court. Hearings on torture allegations may then commence.

With regards to prosecution, as torture and enforced disappearance in the bill are crimes committed by agents of the state, often the police and military, it is extremely rare for any official to be brought to court. The obstacles start at the very beginning of the case as mentioned above.

The final section of the bill therefore focuses on the effectiveness of the prosecution and truth-finding process. Apart from investigators, forensic doctors, medical doctors, and psychiatrists are also part of the team to ensure that evidence of torture and enforced disappearance are properly collected.

The section also states that all cases of torture and enforced disappearance must be handled by prosecutors in Bangkok and tried at the Criminal Court in Bangkok. The law drafter said this is to prevent nepotism and corruption, but some have raised concerns that it would create a huge financial burden for the victims, most of them members of ethnic minorities living on the borders.

Pratubjit said that she gave the bill 8.5 out of 10 and that she is relatively satisfied with it. However, she suspects that the bill will go nowhere in the military-appointed parliament.

Read related story: