Emergency measures adopted to combat the COVID-19 pandemic have been repeatedly used by Thai authorities to target government critics and peaceful protesters, said ARTICLE 19. Police have initiated criminal proceedings against at least 25 individuals involved in peaceful protests for alleged violations of emergency regulations. Today’s decision to extend the emergency period heightens concerns that the pandemic is being used as a pretext to silence government critics.

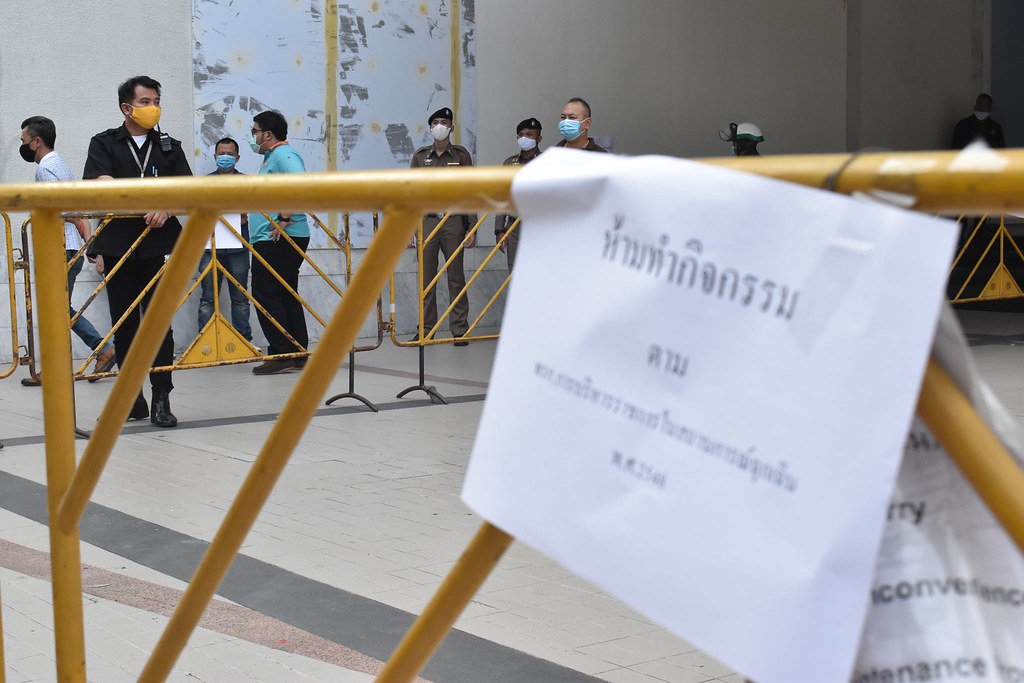

A sign on the metal fence in front of the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre says "activities are prohibited according to the 2005 Emergency Decree." It had been placed there in anticipation of a commemoration event on the 6th anniversary of the 2014 military coup. (Source: Museum of the Commonners)

“As the virus has receded in Thailand, authorities have ratcheted up the pressure on student activists and government critics,” said Matthew Bugher, ARTICLE 19’s Head of Asia Programme. “Measures ostensibly aimed at protecting the Thai people from a public health threat are being used to harass and obstruct peaceful protesters calling for justice and accountability.”

In March, the Thai government invoked the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situation, B.E. 2548 (2005) (Emergency Decree) to declare a state of emergency and implement a set of regulations aimed at combatting the spread of COVID-19. The measures, which went into effect on 26 March, closed bars, stadiums and other public venues, prohibited the hoarding of goods, and restricted international travel.

ARTICLE 19 raised concerns about a provision that prohibits the sharing of news that is ‘false or may instigate fear among the people’, warning that it threatened the right to freedom of expression and access to information. The emergency measures also ban public gatherings, stating that, ‘It is prohibited to assemble, to carry out activities, or to gather at any place that is crowded, or to commit any act which may cause unrest’.

Violations of orders made under the Emergency Decree are punishable by up to two years’ imprisonment.

The emergency declaration was extended for one month at the end of April and another month at the end of May. Last Thursday, the National Security Council recommended a further extension to 31 July, even though Thailand has not recorded a domestically transmitted case of COVID-19 in more than a month. The Centre for Covid-19 Situation Administration agreed to the extension today, and it is expected to be approved by the Thai Cabinet tomorrow.

Since the emergency measures were adopted, Thai authorities have initiated criminal proceedings against at least 25 individuals for their role in peaceful protest activities. Many of those facing charges have been involved in protests concerning the 4 June abduction of exiled Thai activist Wanchalearm Satsaksit in Cambodia. Wanchalearm, a pro-democracy activist who fled Thailand after the May 2014 military coup, was forced into a car by armed men outside his apartment in Phnom Penh. His abduction follows the disappearance and death of Thai exiles in Vietnam and Laos.

Parit Chiwarak, Jutatip Sirikhan and Panusaya Sithijirawattanakul, activists from the Student Union of Thailand, were summoned by police under the Emergency Decree after participating in a 5 June rally in central Bangkok calling for justice for Wanchalearm. The three, along with another activist, were also arrested and charged under the Emergency Decree for a 8 June protest, only to have the charges dropped and replaced by charges under the Maintenance of the Cleanliness and Orderliness Act. The activists have also reported surveillance and unannounced home visits by police officers.

Ten other activists were called for questioning under the Emergency Decree after protesting Wanchalearm’s disappearance in front of the Cambodian Embassy in Bangkok on 8 June. A university student has been charged with violating the Emergency Decree for a protest in Rayong involving a sign reading ‘Who Ordered the Abduction of Wanchalearm Satsaksit?’

Activists have also been charged for protests relating to other issues. On 28 April, an anti-mining activist was questioned by police and threatened with charges under the Emergency Decree after organizing a protest against mining operations in Chaiyaphum province. At least eight prominent political activists and a former member of parliament have been arrested or summoned under the Emergency Decree in relation to commemorations of the tenth anniversary of the deadly crackdown on “Red Shirt” protesters in Bangkok.

Authorities have also cited the emergency declaration as justification for denying permission to hold assemblies, including a gathering to protest the construction of a sea-wall in Songkhla province and a commemoration of the Tiananmen Square massacre in China.

Since the emergency measures were imposed in March, Thai authorities have also taken steps to restrict expression concerning the COVID-19 pandemic. The emergency measures empowered officials to initiate criminal proceedings against those spreading false information under the Emergency Decree or Computer Crime Act, a repressive law that has frequently been used to stifle dissent. Thai Lawyers for Human Rights and ARTICLE 19 have documented criminal proceedings against 42 individuals who made comments about the virus or the government’s response to the virus on social media or other online platforms. One of these individuals is Danai Usama, an artist who made a Facebook post about the lack of screening measures at Suvarnabhumi Airport upon his return from Barcelona and now faces charges under the Computer Crime Act.

Given the current circumstances in Thailand, restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly cannot be justified on public health grounds. Thailand should immediately revoke emergency measures imposing such restrictions and end all criminal proceedings against those targeted merely because of their exercise of those rights.

“The government is giving Thais the green light to pile on to crowded trains and spend Sunday afternoons at the mall, while at the same time charging activists that gather in far smaller numbers,” said Matthew Bugher. “The danger to protesters in Thailand is not COVID-19, but a government intent on silencing its critics.”

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”