“Watching too many movies”

Abdullah Isomuso from Saiburi District, Pattani Province, detained under Martial Law for suspected involvement in insurgency on July 20, was found unconscious in the interrogation centre inside Ingkhayutthaborihan Fort.[1] On the morning of 21 July, when Abdullah’s family visited him in the Fort, they were informed that he had been rushed to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of Pattani Hospital. As his condition deteriorated, he was sent to the hospital of Prince of Songkhla University in Hat Yai, where he lay unconscious until he finally passed away on 25 August.[2] Abdullah was the only son of his handicapped and widowed mother, and his wife was left with small children of 7 and 2 years old.[3]

The unnaturally drastic deterioration in Abdullah’s health happened inside Ingkhayutthaborihan Fort, described as a ‘notorious’ detention centre ‘where suspects are taken for interrogation and held under emergency laws and where rights groups have documented torture.’[4] What actually happened to Abdullah there is difficult to know. The CCTV footage was conveniently not available, as the cameras installed inside the centre were not functioning at the time the incident happened.[5] Answering a question about the involvement of security officers in torture of the suspect, Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha dismissed such suspicions as something caused by ‘watching too many movies’.[6]

In fact, there is no need to watch even a single movie to connect cases of unnatural death or unnaturally drastic deterioration in health with torture. It is just enough to follow what has happened to suspects detained under the special laws enforced in the conflict area of the southern border provinces. Abdullah is not the first case. Several similar cases happened before him, and allegations of torture have never gone away.[7] The National Human Rights Commission stated that during the period between December 2016 and May 2018 there were 100 petitions concerning bodily harm or torture from detainees under the special laws.[8]

An unbridgeable gap of ‘facts’

What Prayut said reflects an almost unbridgeable gap of opinions about this case. The government has persistently denied any allegations of torture or responsibility of security officers in Abdullah’s sudden deterioration in health and his death. On the other hand, many local Malay Muslims in the southern border provinces, human right activists and those who are aware of this issue find the explanations provided by the government highly lacking in credibility. ‘This case can be explained by the facts,’ said Col Pramot Phrom-in, the spokesperson of ISOC Region 4.[9] However, the ‘facts’ convenient for the security forces are not credible to the public, because the very ‘fact’ that caused Abdullah’s state of unconsciousness has never been explained.

The security personnel at every level followed the same line. When asked about Abdullah’s case, Prime Minister (and Minister of Defence) Prayut Chan-o-cha said “the government has said all along it does not have a policy to use violence on suspected individuals or suspects.”[10] The spokesperson of the Ministry of Defence, Lt Gen Khongcheep Tantrawanit, also told the media the same thing, stating that any action outside the country’s law or human right violations by officers would be severely punished.[11] A statement in the same tone had already been issued by the spokesperson of ISOC Region 4 after Abdullah was found unconscious.[12] The absence of a policy, however, does not guarantee that there is no misuse of power, no human right violations or no torture in practice.

Although the readiness of the government to punish any officer involved in misbehaviour, misuse of power or human right violations has been repeated again and again whenever a similar suspicion arises, it lacks the very basis to convince the public because no officer has ever been punished to this day.[13] According to Zachary Abuza, “a handful (of soldiers) have been (prosecuted for alleged torture or death of inmates in its custody), but all have been freed on appeals.” He continued, “In most cases, after government pledges to investigate, charges are dropped after public pressure dissipates.”[14] It seems that this time the government is following exactly the same script.

In Abdullah’s case, even the investigation process is questioned. ISOC Region 4 set up a fact-finding committee to investigate, including local religious leaders and NGO activists including human right activists. However, a fact-finding committee on a case that happened inside a military facility by the military itself is not sufficiently convincing or credible.[15] Rungrawee Chalermsripinyorat, a freelance researcher focusing on the conflict, questioned the method of investigation.[16] The committee had to face a diminution of its already thin credibility after the resignation from the committee of Anchana Hemmina, a local human rights activist, due to the restrictions in accessing information.[17] She told the BBC that the purpose of the investigation is justice for the deceased and his family, not the protection of anyone or any government agency. Therefore, the important thing is to investigate what rendered him unconscious, not the (medical) reason of his death.[18] Dr Chalita Bundhuwong, a lecturer in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Kasetsart University, stated in her Facebook post on 28 August that involvement of local civil society organisations (CSOs) and religious leaders in the committee was to provide justification for the army.[19]

The government is trying to convince the public that officers were not responsible for Abdullah’s condition, but questions about how Abdullah became unconscious while in military detention remain unanswered. The renovation of the interrogation centre into a place resembling a ‘home or a resort’ hardly helps anything.[20] The gap of opinion between the government and the public seems bigger and bigger. As can be observed from Prayut’s statement, the government apparently fails to grasp the seriousness of the impact caused by Abdullah’s death.

Abdullah as a public figure of the conflict area

Before he was detained, not many people knew Abdullah. Now he is known among most of the local people, and his death was reported by the mainstream media. The impact of the tragedy that has befallen Abdullah and his family can be seen from two prayer ceremonies held for them.

On 24 July, more than a month after Abdullah was rushed to the ICU, the local community of his village organised a prayer ceremony to pray for his health and recovery and the strength of his family. [21] By that time local Malay Muslims understood that Abdullah’s brain had been severely damaged, and he was kept alive only by the assistance of various medical devices. The only possibility of his recovery was miraculous help from God. The ceremony was attended by several hundreds of people. The prayer was led by Waedueramae Maminchi, President of the Islamic Council of Pattani Province, joined by local politicians (including former and incumbent MPs) and religious leaders.[22] Abdullah passed away the next day, 25 August. The funeral prayer in a mosque near his house was attended by more than a thousand people.[23] The funeral of an ordinary villager is usually attended by a few hundred. The number of mourners who attended Abdullah’s funeral prayer indicates that he has become a public figure for the Malay Muslim community in the conflict area.

The tale of Abdullah and its position in the local discourse

The tale of Abdullah and his family’s suffering has become a part of the history of the Patani Malay Muslims’ long-suffered grievances, and like so many similar tales before him, it will be related again and again. Although his body was washed before the burial (unlike the body of a martyr, which is buried without being washed), in the perception of nationalistic Malay Muslims in the south, he is almost like a martyr.

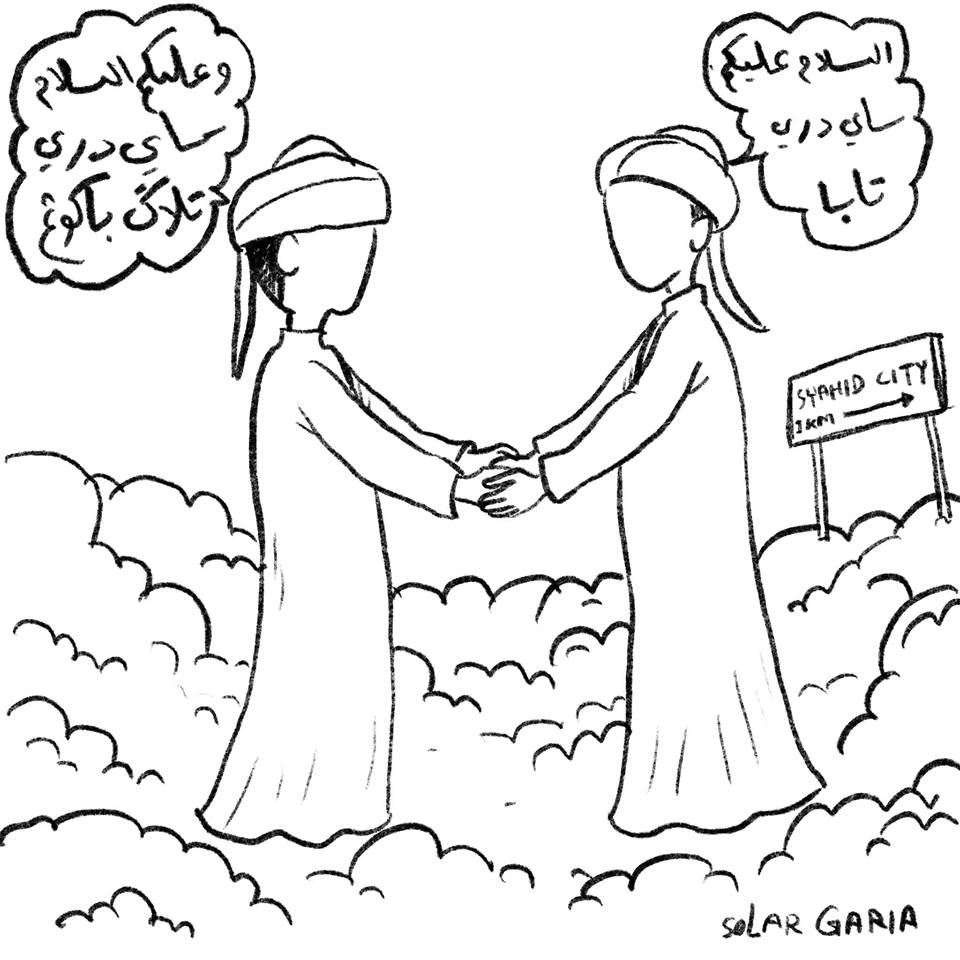

On 22 July, after reports of serious damage to Abdullah’s brain caused by a lack of oxygen for a long period of time, a local activist posted a picture of two Muslim men shaking hands with each other, standing on a cloud. In the background, there is a signboard to ‘Syahid City (City of Martyrs)’. In the captions written in the Jawi script of Malay,[24] a man from the city welcomes a newcomer and says, “Assalamualaikum (Peace be upon you). I’m from Tak Bai”. The newcomer says, “Waalaikumussalamm (And upon you peace). I’m from Telaga Bakong”. Telaga Bakong is the Malay name for Bo Thong, the name of the subdistrict (tambon) where Fort Ingkhayutthaborihan is located. The significance of this picture lies in the fact that although Abdullah had nothing to do with the brutal crackdown on the demonstrators in Tak Bai on 25 October 2004, in the perception of local Malay Muslims, these incidents can be so readily connected with each other.

Picture posted by Solar Garia on his Facebook page, 22 July 2019

In the Tak Bai case, the Songkhla Provincial Court only stated that the officers transported the hundreds of the demonstrators who were “stacked like cordwood in the back of army trucks”[25] to Ingkhayutthaborihan Fort ‘out of the necessity of the circumstances’ and they died due to the lack of oxygen: the same reason that rendered Abdullah unconscious. So far not a single officer has ever been punished for the death of 78 demonstrators[26]. Even when Abdullah was still alive, given his grave condition, some people believed that he should be granted God’s mercy in heaven like the demonstrators in Tak Bai who are generally regarded as martyrs.[27]

After Abdullah passed away, the president of the Patani United Liberation Organisation (PULO), Kasturi Mahkota, posted a condolence message on his Facebook page. The last sentence reads, “We pray that Abdullah will be placed in the company of the prophets, the martyrs and the righteous.”[28]

For the insurgents, one of the most challenging aspects in their struggle is recruitment. The process of finding, inviting, indoctrinating and training new members has never been easy. A BRN political leader from Narathiwat Province explained to the author that it had been difficult to convince young Malay Muslims of the cruelty of the ‘Siamese colonisers’ before 2004. They had to tell the stories of Patani Malays’ grievances from the past, but faced difficulties in finding more recent examples of alleged cruelties. The tide changed after the crackdown on the Tak Bai Demonstrators. They no longer had to explain the cruelty of the Thai government and relate the stories of the past, but only had to say, ‘Look at what happened in Tak Bai.”[29] Any incident that is perceived as an example of the cruelty of the state is immediately added to the discourse of Patani Malays’ historical grievances. There is no reason for the insurgents to refrain from citing Abudllah’s case as the latest example.

The impact of Abdullah’s death on the conflict

The conflict in the southern border provinces will never be solved unless this discourse of Patani Malays’ history of grief is properly addressed. Under the current circumstances, it is highly unlikely that any credible and acceptable explanation of how Abdullah became unconscious in the military interrogation centre will be provided. Accordingly, as in previous cases, it is almost unimaginable that any officer will be punished. As was explained above, any incident that indicates injustice or an atrocity committed by the state, such as extrajudicial killing, arbitrary detention, torture, or the mysteriously sudden deterioration in the health of a detainee, is integrated into this discourse, and Abdullah’s case fits perfectly into this context. Romadon Panjor, the editor of Deep South Watch, pointed out that the security forces recently designated pondoks[30] and private Islamic schools as breeding grounds of insurgents, but failed to see that the interrogation centres of the security forces also have become breeding grounds by producing the narrative of injustice that is needed by the insurgents.[31]

The Southern Border Provinces Administrative Centre (SBPAC) has promised to pay THB 500,000 as so-called ‘assistance money’ - compensation paid to victims of the conflict without acknowledging any responsibility of the state - to Abdullah’s family and financially support the education of his children.[32] This kind of remedy provided by the state is better than nothing, but paying money to a victim’s family is still very far from justice.

In addition, if a detainee’s health can deteriorate in such an unexplained way and no justice is guaranteed, those who are marked by the security forces also might choose to escape.[33] The escape route either can be to Malaysia, or in more radicalised cases, to the forest to join the insurgent armed forces.

A ‘half-baked amnesty’ scheme[34] called the ‘Bring People Home Project’ was launched by ISOC Region 4 in September 2012 to encourage insurgents to surrender.[35] Insurgents might surrender to the government only when they can trust that justice will be delivered by the government. What happened to Abdullah goes against this scheme, as it severely reduces the local population’s trust in the state justice system.

Zachary Abuza noted that “the death of suspects in custody always begets retaliatory violence, especially against Buddhist civilians”, because “If the insurgents don’t respond – i.e., come to the defense of one of their own, or at least one of the constituents they claim to represent – they look weak.” [36]

Abdullah’s case cannot be dealt with just by setting up an unreliable fact-finding committee under military supervision, asserting the absence of a policy to torture suspects detained under martial law, and to provide medical conditions that caused death. It has become a part of the conflict, and we have to realise how far we still are from peace.

[1] Prachatai English, 25 July 2019, “Suspected insurgent admitted to ICU after being held in military camp”. https://prachatai.com/english/node/8150

[2] Prachatai English, 26 Aug 2019, “Suspected insurgent dies after 35 days in ICU”. https://prachatai.com/english/node/8184

[3] BBC Thai, 26 August 2019, “ซ้อมทรมาน : จากควบคุมตัว หมดสติ ถึงเสียชีวิต เกิดอะไรขึ้นกับ อับดุลเลาะ อีซอมูซอ”. https://www.bbc.com/thai/thailand-49470456?fbclid=IwAR11aBUNWLnknlnU10NzKyZnirQagF3W02Hmz9stwsu60f3B3bPSYps9618

[4] New Straits Times, 26 August 2019, “Muslim man dies after Thai army interrogation”. https://www.nst.com.my/world/2019/08/515898/muslim-man-dies-after-thai-army-interrogation?fbclid=IwAR25owmPhwC-vrp8UVx70OuIjEZRpe8S4mNmE71b5AFJwM9wS_RNYKIGsO4

[5] Thai PBS, 26 August 2019, “ฮิวแมนไรต์วอตช์ จี้ตั้งกรรมการอิสระสอบปมเสียชีวิต "อับดุลเลาะ"”. https://news.thaipbs.or.th/content/283364?fbclid=IwAR0qUkpMEAk5ovk6IO2-OMOqmnRjwPxL4UUTLwcAc_1pTMH4hq_V-b0tkbI

[6] BBC Thai, 31 July 2019, “ซ้อมทรมาน : คกก.คุ้มครองสิทธิฯ แถลงกรณีอับดุลเลาะ อีซอมูซอ หมดสติระหว่างถูกคุมตัว ตัดประเด็น "อุบัติเหตุ-ลื่นล้ม"”. https://www.bbc.com/thai/49175954

[7] Hara, Shintaro, 5 Aug 2019.,“The return of an unconscious body”. https://prachatai.com/english/node/8161

[8] BBC Thai, 26 August 2019, Ibid.

[9] Manager Online, 25 August 2019, “กอ.รมน. ภาค 4 สน. ดึงสติฝ่ายค้าน ปัดฆ่า “อับดุลเลาะห์ อีซอมูซอ” ผลชันสูตรปอดติดเชื้อ” https://mgronline.com/politics/detail/9620000081374?fbclid=IwAR2dwta5WnfVrV_d0ixbdGOGsRth1pNXIXX8QG0W29II9kwiLP49LVLY2eg

[10] Benar News, 27 August 2019, “Thai PM Rejects Torture Allegations in Rebel Suspect’s Death”. https://www.benarnews.org/english/news/thai/Rebel-suspect-death-08272019162314.html

[11] Manager Online, 26 August 2019, ibid.

[12] Benar News, 22 July 2019, “Thai Deep South Suspected Rebel in Coma after Arrest, Interrogation”. https://www.benarnews.org/english/news/thai/suspect-hospitalized-07222019170223.html?fbclid=IwAR2k50n95gnncEyTF-YBklAxRApmb27MZsVEW3SxqerUA_M2ZmxaF8LCIuw

[13] For further discussion, see Hara, 2019. Ibid.

[14] Zachary Abuza, 27 August 2019, “Suspect’s Death in Army Custody Likely to Incite Deep South Insurgency Commentary”. https://www.benarnews.org/english/commentaries/asean-security-watch/Zachary-Abuza-08272019163728.html

[15] Talk News Online, 29 August 2019, “นักวิชาการยะลา มองปัญหาอับดุลเลาะ คณะกรรมการตรวจสอบต้องมาจากรัฐสภามากกว่า คณะกรรมการที่ได้มีการแต่งตั้งในพื้นที่”. https://www.talknewsonline.com/151170/?fbclid=IwAR09Il-TdXRAMIjSkms2-pxD6TTMCWETWoiDC_PkKyu7h1unLaL5s0xRdB8

[16] BBC Thai, 28 August 2019, “ซ้อมทรมาน : ผลสอบสวนกรณี "อับดุลเลาะ" หมดสติ-เสียชีวิต สร้างความคลางแคลงใจ”. https://www.bbc.com/thai/49500002

[17] Thai PBS, 28 August 2019, “"อัญชนา" ลาออก กรรมการคุ้มครองสิทธิมนุษยชนจังหวัดชายแดนภาคใต้”. https://news.thaipbs.or.th/content/283467?fbclid=IwAR1ZKIaAI03Tv6s0Ymcb-nrd1Rkk4FoARxRp67ZAHBGlHmZwdUKNPj0toJY

[18] BBC Thai, 28 August 2019, Ibid.

[20] Manager Online, 28 August 2019, “ไปเที่ยวกันไหม! ปรับ “หน่วยซักถาม” ค่ายอิงคยุทธบริหารเป็นแหล่งท่องเที่ยว ไม่มีทรมาน ติดกล้องพร้อมใช้งาน” https://mgronline.com/south/detail/9620000082590?fbclid=IwAR37pKVEC-8fory5YkpKVqjzxTILFifmtXFeR9jFM7foPTqngdGoEic9xTU

[21] The prayer is called ‘salat al-hajah’, or Prayer of Need, addressed to God through intermediaries. See Oxford Islamic Studies Online. http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e2079

[22] Manager Online, 24 August 2019, “แกนนำมุสลิมร่วมละหมาดฮาญัตขอพรให้ “อับดุลเลาะ” ฟื้นกลับมาอยู่กับครอบครัวอีกครั้ง” https://mgronline.com/south/detail/9620000081104

[23] Khaosod, 25 August 2019, “นับพันแห่ร่วมละหมาดศพอับดุลเลาะ หมดสติในค่ายทหาร ญาติเศร้าขาดเสาหลัก” https://www.khaosod.co.th/around-thailand/news_2834354

[24] A traditional Malay script adopted from that of Arabic with some additional letters.

[25] Bangkok Post, 16 October 2017, “Dress the Tak Bai wound”. https://www.bangkokpost.com/opinion/opinion/1343067/dress-the-tak-bai-wound

[26] Prachatai, 30 May 2009, ““ขาดอากาศหายใจ” การขนย้าย เป็นความจำเป็นแห่งสภาพการณ์แล้ว”. https://prachatai.com/journal/2009/05/24394

[27] For further discussion on the concept of martyr in Patani, see Hara, Shintaro, 2019, “The interpretation of Shahid in Patani”. Asian International Studies Review. Vol. 20. Special Issue (June 2019): 137-157.

[28] See the full text (in Malay and English) at https://web.facebook.com/kasturi.mahkota/posts/2422983384447030

[29] Personal interview, ex-political leader of BRN, Terengganu, Malaysia, March 2017.

[30] A pondok is a traditional boarding school for Islamic education where religious subjects are delivered in Malay based on textbooks written in Jawi script.

[31] Voice TV, 26 August 2019, “อับดุลเลาะ อีซอมูซอ: การตายที่ต้องมี 'คนรับผิดชอบ'”

[32] Matichon Weekly. 7 September 2019. “ศอ.บต.เยียวยาครอบครัว “อับดุลเลาะ” พร้อมดูแลทุนการศึกษาบุตร 2 คน”. https://www.matichonweekly.com/hot-news/article_226762

[33] The Reporters (Facebook page), 28 August 2019, https://web.facebook.com/TheReportersTH/posts/2391938087723244

[34] Don Pathan, 29 March 2018, “Southern Thai Peace Talks Hit Snag Over Rebel Group’s Demand”. https://www.benarnews.org/english/commentaries/far-south-view/Don-Pathan-03292018112213.html

[35] Thai Civil Rights and Investigative Journalism, 20 January 2018, “‘พาคนกลับบ้าน’ ลดช่องว่าง-สร้างความเข้าใจ ได้จริงหรือ?” https://www.tcijthai.com/news/2018/20/scoop/8164

[36] Abuza, 2019, Ibid.

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”