Commemoration events for the May 2010 crackdown on the ‘red shirt’ protest began on the afternoon of 19 May 2019. Activist Sombat Boonngamanong arrived at the Ratchaprasong McDonald’s with a sign calling for Abhisit Vejjajiva, former head of the Democrats Party and Prime Minister at the time of the 10 April and 19 May 2010 crackdowns, to apologize for the violence against civilians.

The gathering in front of Gaysorn Plaza, in the evening of 19 May 2019

In the evening, a crowd gathered at Ratchaprasong Intersection, in front of Gaysorn Plaza. On the right side, by Ratchadamri Road, a group led by Anurak “Ford” Jentawanich and Ekkachai Hongkangwan gather to sing in a symbolic act. Meanwhile, on the left side, by Ploenchit Road, an assembly was held by the leaders of the People Calling for Election group, including activist Nuttaa Mahattana, Sirawit Serithiwat, Future Forward MP Rangsiman Rome, and former Thai Raksa Chart MP candidate Tossaporn Serirak.

And at the Ratchaprasong Intersection sign, Phayao Akhad and Pansak Sritep joined the peaceful gathering, which ended after candles were lit in memory of the victims of the crackdown.

Phayao’s daughter Kamonked was a volunteer nurse during the May 2010 demonstration and was among those killed at Wat Pathum Wanaram on 19 May 2010, while Pansak’s son Samapan, also known as “Cher”, was shot and killed near Soi Rangnam on 15 May. Nine years on, there is still no justice.

What happened in May 2010?

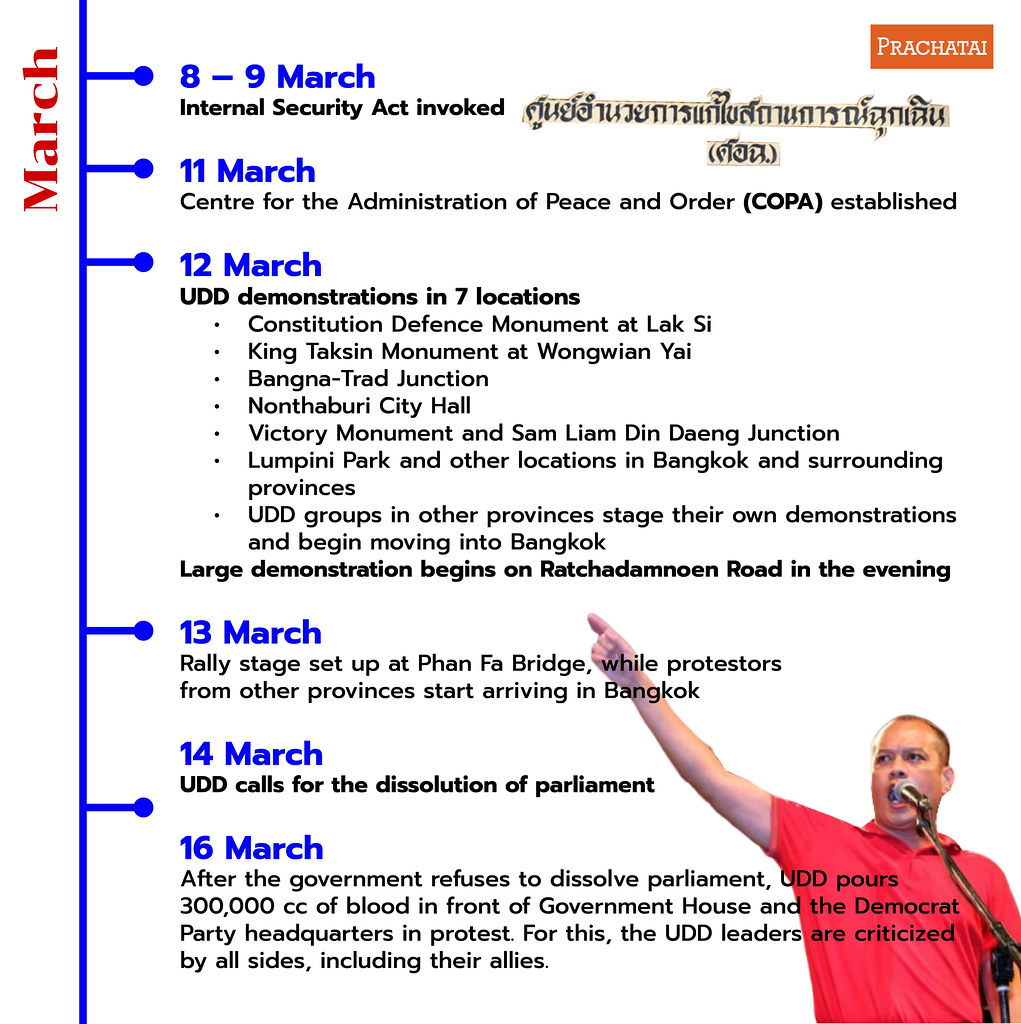

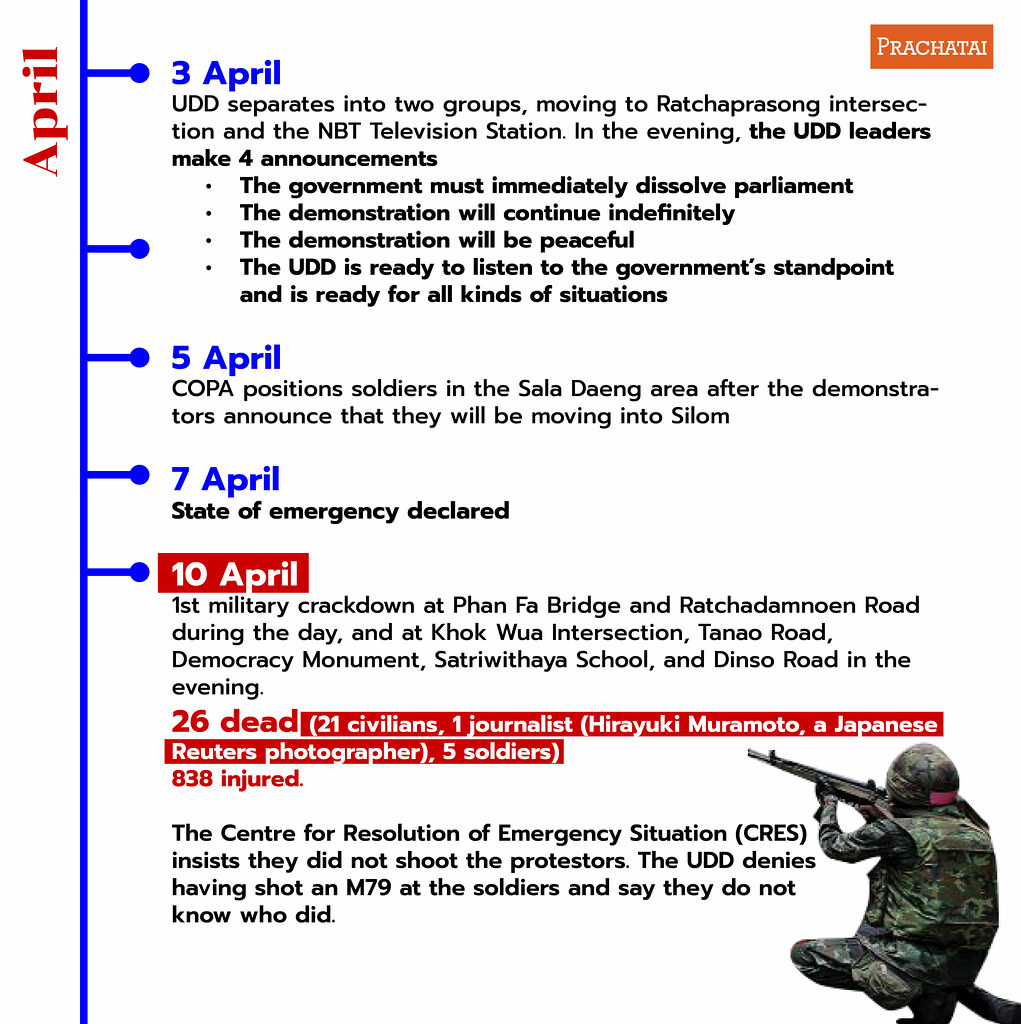

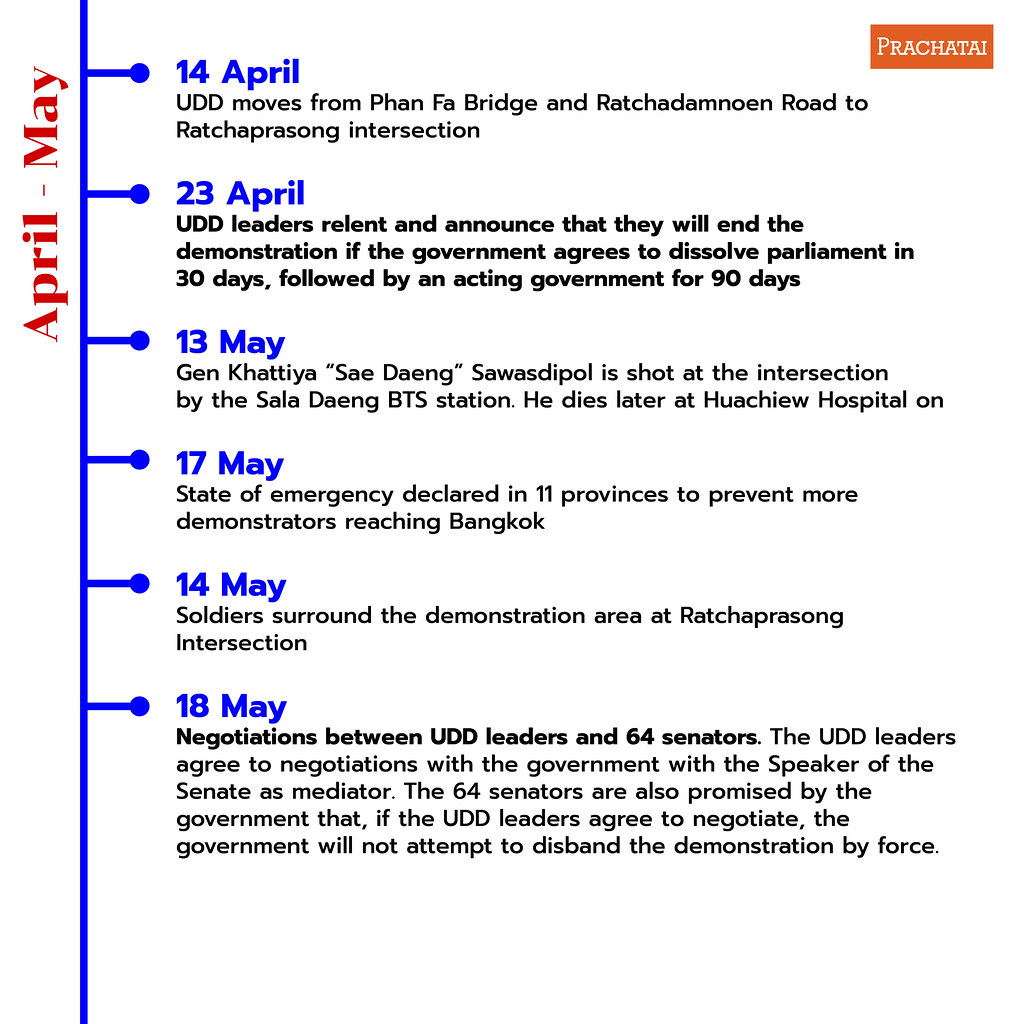

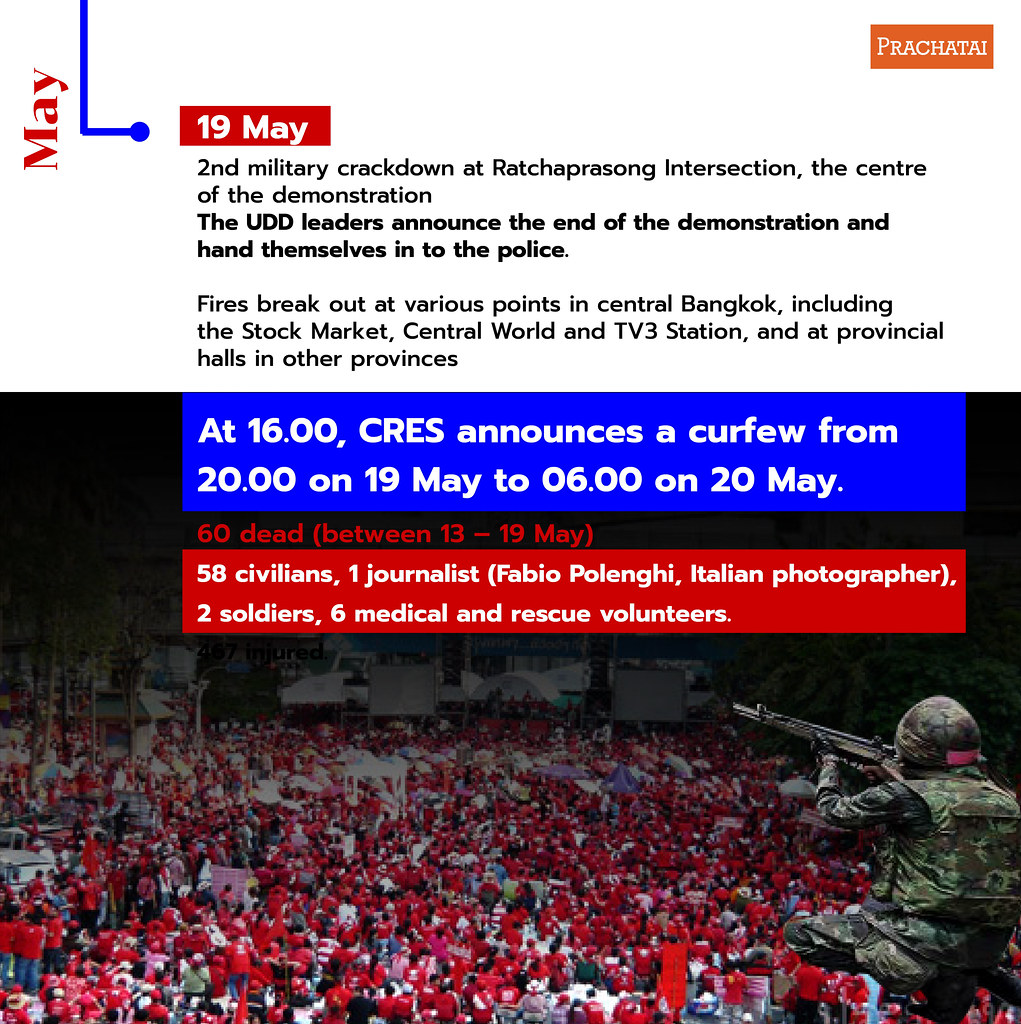

The events of 19 May 2010 were the culmination of a three-month long demonstration by the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD) beginning around the end of February 2010 against the government led by Abhisit. The following timeline is a summary of what happened between February – May 2010.

The use of military force against the UDD protestors is considered one of the most violent suppressions of a mass demonstration in contemporary Thai history. The Abhisit government claimed that the protestors were ‘terrorists.’ However, news reports, pictures, and video footage of the scene show that none of the victims were armed. No weapons were found near the bodies of the protestors, and until now, no trace of gunpowder has been found on any protestors’ hands. Human Rights Watch’s May 2011 report “Descent into Chaos: Thailand’s 2010 Red Shirt Protests and the Government Crackdown” documented excessive and unnecessary force used by the military that caused many deaths and injuries during the 2010 political confrontations. The high number of casualties—including unarmed protesters, volunteer medics, reporters, photographers, and bystanders—resulted in part from the government’s enforcement of “live fire zones” around the UDD protest sites in Bangkok, where sharpshooters and snipers were deployed.

According to the People’s Information Centre: April–May 2010 Crackdowns (PIC), 94 were killed and almost 2000 were injured in April and May 2010. Around 80% of those killed were civilians and more than 60% were killed between 13 – 19 May.

Among those killed were 6 medical and rescue volunteers: Boonting Pansila, Mana Saenprasertsri, Warin Wongsanit, Mongkol Khemthong, Akkaradet Khankaew, and Kamonked Akhad. The direct attack on medical and rescue personnel obstructed the work of emergency response teams, leading to the death of critically wounded individuals who required urgent medical attention, many of whose lives could have otherwise been saved.

Not only that, attacks on medical and rescue personnel on duty in conflict zones are a violation of international norms. Under customary international humanitarian law, medical personnel assigned to medical duties must be respected and protected in all circumstances, even in non-international conflict.

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, to which Thailand is a signatory state, but has yet to ratify the treaty, also states that intentional direct attacks against buildings, material, medical units and transport, and personnel using the distinctive emblems of the Geneva Conventions in conformity with international law constitute a war crime.

Among the emblems of the Geneva Conventions is the symbol of the red cross, an internationally recognized symbol of the protection that international law confers on the wounded and the sick and those caring for them in times of armed conflict. And yet, Kamonked Akhad, who was wearing a vest with the red cross symbol while working at the medical tent at Wat Pathum Wanaram, was found to have been shot at least ten times.

There were also 2 journalists among those killed: Hiroyuki Muramoto, a Japanese Reuters photographer killed on 10 April, and Fabio Polenghi, an Italian independent photographer, killed on 19 May.

Article 79 of the Additional Protocol (I) to the Geneva Conventions states that journalists on duty in conflict zones are recognized as civilians and are therefore entitled to the same protection under customary international law, as long as they do not take a direct part in the hostilities. Violating this rule is therefore a serious breach of the Geneva Conventions and of international norms. In addition, intentionally directing an attack against a civilian also amounts to a war crime under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

‘Justice delayed is justice denied’

For the victims of both the April and May crackdowns and their families, justice has been delayed for the past nine years.

The Bangkok Criminal Court has already ruled on the cases of 29 victims out of 94. In this number, the court inquests for 17 victims found that they were killed by military fire, but no specific military personnel have been identified as the culprit. On 4 May 2019, the military prosecutor also decided not to indict eight soldiers accused of fatally shooting six civilians in Wat Pathum Wanaram on the ground that there was no evidence and no witnesses to the killing – a direct contradiction of the Bangkok Criminal Court’s August 2013 inquest, which found that the residue of bullets inside the victims’ bodies was the same type of ammunition issued to soldiers operating in the area at the time of the shooting.

“Despite overwhelming evidence, Thai authorities have failed to hold officials accountable for gunning down protesters, medics, and reporters during the bloody crackdown in 2010,” said Brad Adams, Human Rights Watch’s Asia director. “The military prosecutor’s decision to drop the case against eight soldiers is the latest insult to families of victims who want justice.”

Phayao Akhad wearing her daughter's blood-stained nurses gown at a demonstration on 30 August 2017 (Source: Human Rights Watch)

Meanwhile, Phayao Akhad, who has always been actively campaigning for justice for her daughter and the other victims of the crackdowns, said that she will be continuing her campaign to bring charges against those responsible for the death of the protestors.

We remember: voices from the commemoration gatherings on 19 May 2019

And we return to the Ratchaprasong Intersection on 19 May 2019, where the crowd – some of whom were wearing red shirts – gathered in memory of the dead.

Lek came to the gathering with a sign saying “10 April – 19 May ’10: 9 years of the brave heroes who fought for democracy, the red shirt people.” He was also at the 2010 protests and said that he is still hurt by what happened.

“My friends died, but there is still no progress. For me, it’s like the pain is still there,” Lek said. “I am not vengeful. I don’t hold a grudge. But I realize that, if my friends are hurt, I am also hurt. Since my friends died and I live, why should I not want justice for them? This is what I want to do here. I’m not challenging anyone. I’m not fighting anyone. They do their job. I do mine. My job is to fight for what happened in the past.”

Meanwhile, a 76-year-old man who asked not to be named said that he was also at the 2010 protest and that he would come to the commemoration event every year for as long as he lives.

“I came here to remember the worst day of my life,” he said.

Nuttaa Mahattana was not at the UDD protests, but as a leading member of the People Calling for Election group, Nuttaa is one of those holding an event in memory of the dead.

“I never went to any protest with the red shirts, but when there are losses, I wanted to come to the commemoration event since the first year, to show respect for the dead and to demand justice for them,” said Nuttaa, “so I came to light the candles every year. This year, it’s a bit more active, because there are young people here taking in letters to the Senate as well.”

25-year-old Sasiphat Pongpraphapan said he came to the commemoration event every year. “The injustice done against them has not be fixed, so we have to organize events so that they know someone thinks of them, and that this should not have been done against them,” he said. “No one deserves to die, because we share the same ideology. In the future, I hope that they will get justice. Everyone must be able to get justice.”