Story by Nalutporn Krairiksh

Photos by Kotcharak Kaewsurach and the Mirror Foundation

“If Uncle Uan is gone, who will give us the winning numbers?”

An auntie in the neighbourhood cited Uncle Uan’s function while the police were taking him to Somdet Chao Phraya Hospital.

Uncle Uan is a fifty-something-year-old big man of dark complexion, appearing much darker for not having had a bath for quite some time. We and the Mirror Foundation Street Patients Project met to take him to hospital after receiving a report that he might come to harm if he kept on sitting on this small bridge.

The tracing-acquainting-hospitalizing process

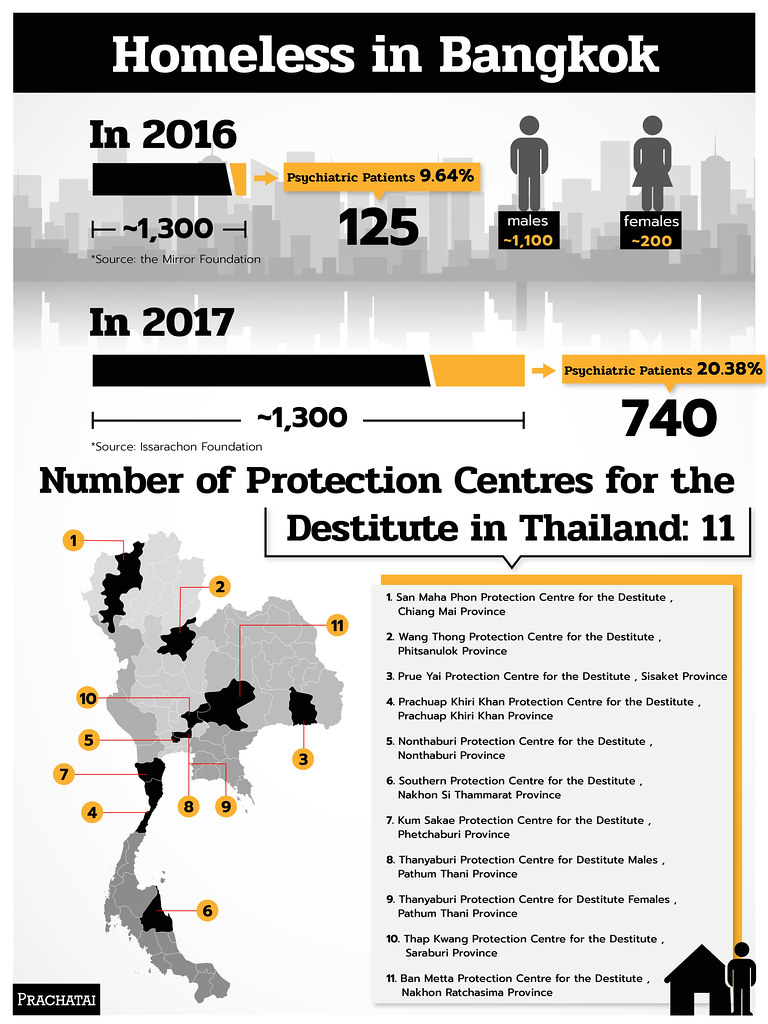

Some of the mad street people, as they are called by many, are psychiatric patients who have run way from home. Many of them do have homes and families, but due to a variety of circumstances, pressure and reasons, their homes are not where they choose to be. Statistics of the Mirror Foundation show that in 2016 there were approximately 1,300 homeless people in Bangkok; 202 of them were women and 9.64 percent, or 125, were psychiatric patients. In 2017, however, the Issarachon Foundation reported an increase of the total number of homeless people in Bangkok to 3,630, and out of this, 740 were psychiatric patients.

Homeless in Bangkok

Sittipon Chuprajong of the Mirror Foundation recounted that when he started to work with homeless people, he soon realized that a large number of them had symptoms of psychiatric disorder, and that was the birth of the Street Patients Project to work with this group in particular. Because they live by the roadside, the problems they have encountered include physical assault, being chased away, sexual abuse, or mistreatment as if they were playthings, but the street patients still need to remain there. If they show up in public places, people would keep their distance in order to feel safe.

The problem of being unidentifiable means that by the time they are reported and admitted to a treatment process, their symptoms have already worsened. Many hear voices, hallucinate, talk to themselves, and start to attack others out of paranoia. Many of them do not know or admit that they are ill.

When the Facebook message box sends a signal that someone has reported a case, the team will investigate in order to separate ‘street patients’ from the other ordinary homeless people, and plan a visit to assess them in order to reduce duplication of work. As a start, 10 questions will be sent back to the reporter seeking photographs, information on gender and age of the patient, time and place of encounter, physical appearance such as clothes, stature, observable behaviour, other information from people in the neighbourhood, and the name and telephone number of the reporter. Afterwards, the team will go to the place to look for the patient in question. If he or she cannot be readily found, the team will walk around and ask people in the area, such as motorcycle taxi drivers, shop owners, etc.

It’s always too late by the time treatment is received

Jai (alias), a young woman wearing a tiger skin pattern jacket walking back and forth between Thong Lo and Asok, has aggressive behaviour, cursing and swearing by herself, appearing menacing to people around her. The symptoms have escalated rapidly as no one had noticed anything amiss earlier until the aggression became more intense.

Jai has to be assessed whether she meets the criteria for hospital admission for psychiatric care or not based on observation of her behaviour, physical condition, and living situation. In addition, interviews with people living in the area provides crucial information.

Each year, the Mirror Foundation has about 20 cases of homeless patients under its care. There are more men than women, and they are migrants from other provinces. Even though the Mental Health Act of B.E. 2551 states that people with a mental disorder can receive treatment from state hospitals or healthcare institutions, in reality, unless they are specialized in psychiatric treatment, state hospitals generally do not admit psychiatric patients as their facilities are already crowded with other patients. Psychiatric patients are therefore automatically referred to just a few specialized hospitals available in each region. Once treatment is completed, the patients will be further referred to government facilities for the destitute in general.

Uncle Uan has been living on the canal bridge for over 10 years, or it could be as long as 20 years, according to residents of the neighbourhood. No one had thought of taking him away from there, no matter how unhygienic it is, because he was good-humoured and always gave them lottery tips. From being chatty and able to take care of himself, his mental ability has deteriorated to the point that his reasons and decisions became erratic. In similar circumstances is Dao (alias), a young woman in a long skirt on a downtown pedestrian bridge; she has been in and out of treatment 3 times in the past 3 months. Her story is complicated and hard to recount. Last month before she gave birth to her child, she was denied admission by a mental hospital and was sent to an ordinary hospital for pre-natal care. She escaped before the due date to go back on the street. No one knew where she was until a newborn baby’s body was found at a bus stop one night. Soon after, she was spotted back on the same pedestrian bridge in the Sukhumvit area. She became better once after the first course of treatment and went back to live with her family for a while before coming back to wander the streets again. She said there was no freedom at home. This time, she has turned from someone who used to talk sense to one who talks nonsense, keeping to herself, surviving by begging.

Gaps in the system, no responsible agency

Some of the street patients do not meet the criteria for hospital admission specified in the Mental Health Act. The phrase ‘persons with mental disorders that shall receive treatment’ is further qualified as those in a dangerous condition in which the mental disorder exhibited through behaviour, emotion, delusional thoughts poses a danger to others’ or his/her own life, body or property. Many times, homeless patients do not run rampage, act aggressively, or harm themselves or others; they are merely unable to care for themselves or protect themselves from harm, maintain hygiene, and gain access to medical care. Such narrow criteria have excluded many patients from proper treatment, allowing their symptoms to worsen. The situation is worse for patients afflicted by other conditions such as pregnancy, physical disease, statelessness, old age, disability etc., as there will be no case worker to follow up on them in the long-run. Such is the case of Dao, who was sent to a hospital that did not understand her mental condition while psychiatric hospitals would not admit her because she was pregnant. She ended up giving birth on the streets before an agency with the exact mandate finally stepped in to take responsibility.

According to the Mental Health Act, a patient can remain under care for 90 days at most; this may be extended for another 90 days if additional time is expected to improve the patient’s condition further. Treatment starts with a doctor’s appraisal of the symptoms, then continues through medication, therapeutic activities and maybe electric shock if the patient agrees to it. Most street patients under treatment cannot identify themselves. Uncle Uan cannot say who he is, where he comes from, not even his own name. They therefore cannot claim benefits from the health security gold card, nor the rights of people with disability or any other rights. If they are lucky, the may get a place in the hospital’s quota for the destitute. But if they are not, then there is no treatment available for them.

As mentioned earlier, even though patients have the right to treatment in any state hospital or health facility, in reality, there are very few psychiatric hospitals available in each region, and they are already overcrowded, especially in the central region. After treatment is completed, patients will be referred to the Protection Homes for the Destitute, with the likelihood of remaining there for the rest of their lives.

No room even to move around in the protection homes

Oi (alias), another young female street patient, is waiting to be accommodated at a Protection Home for the Destitute. While on the streets, she became pregnant and gave birth to 3 children; during the last pregnancy, she was sent to a mother and child shelter, which may not be equipped with sufficient understanding of psychiatric care. A small child in the shelter was slapped by Oi because she was irritated by the loud noises the child made, easily a good stimulant for mental symptoms.

According to Nichapat Wiboonpanich, former Superintendent of Nonthaburi Protection Home for the Destitute, 430 residents are being served in the facility by 29 staff, 5 of them daily carers of psychiatric patients. More than half of the residents are psychiatric patients, the rest are elderly people, persons with disabilities and even young people. The number of psychiatric patients shot up after a provision in the Mental Health Act was passed requiring the Home to admit them as well. Currently, the 5 buildings with a capacity for 350 residents are being used to house 100 each, and the Home is constantly trying to transfer residents to other facilities in the province in order to be prepared to receive new residents as required by the law.

There are 11 such Protection Homes in the whole country. They operate under 3 main laws: (1) the Protection of Helpless Persons Act, 2014, (2) the Control of Begging Act, an old piece of legislation from 1941 that was amended in 2016, and (3) the Mental Health Act, 2008, which stipulates that upon completion of treatment in psychiatric hospitals, patients whose families do not take care of them or provide inappropriate care for them, or for whom there are no families to return to, have to be transferred to agencies responsible for the protection of the destitute. Upon admission, there has to be a follow-up care process for them, including provision of medicine, emergency care, etc.

The two conditions cited above imply that each Home not only has to admit pregnant psychiatric patients like Oi, but also those with additional incapacitating conditions, like disabilities, or being bed-ridden; this burden is well beyond the capacity of the current handful of staff.

Unrealistic rehabilitation

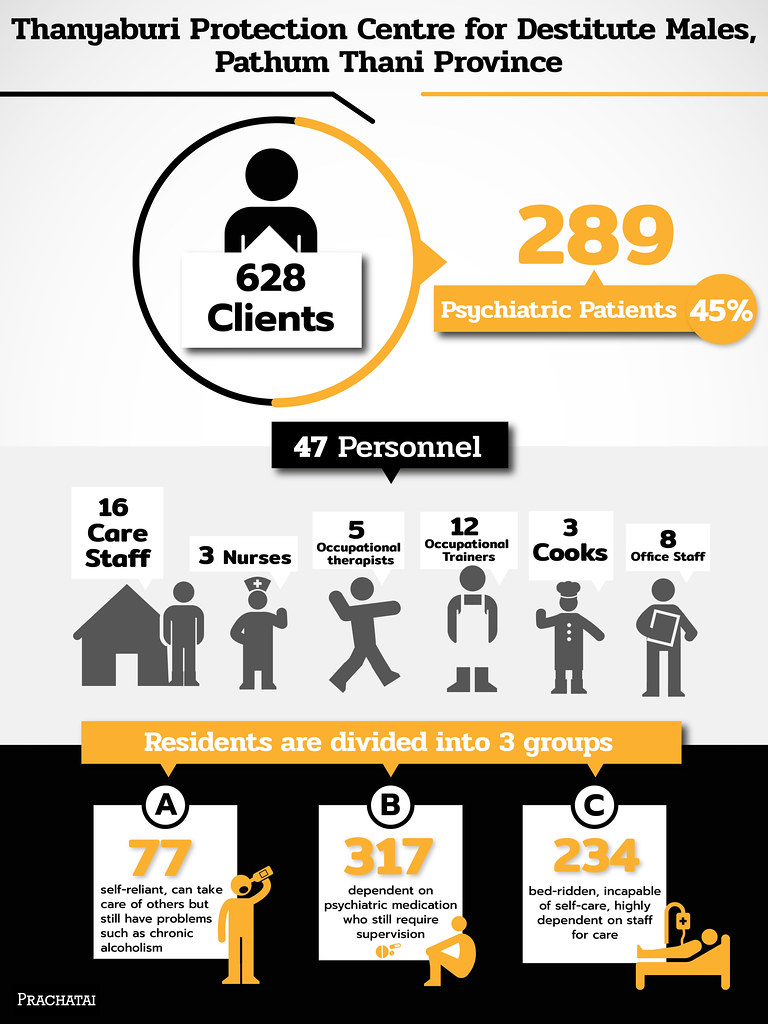

Apart from providing daily care, medicine and other treatment according to the symptoms, the facilities for the destitute also aim to rehabilitate the residents, including psychiatric patients. Uthen Chanakul, former Superintendent of the Thanyaburi Protection Home for Men reported that the Home had several training courses for the residents to learn occupational skills, but the problem was that only a few have been trained each year and none has been able to make a real living with the skills.

Thanyaburi Protection Home for Men

Most psychiatric patients, like Uncle Uan, Jai and Dao, when placed in a Protection Centre, will be divided into A, B and C groups by means of the IRP (Individual Rehabilitation Programme) assessment conducted by psychologists, residence heads, and social workers, who then plan the care needed for each group:

Group A comprises those who can take care of themselves and of others, but have personal problems, such as alcoholism;

Group B comprises dependent patients on psychiatric medication who need supervision and is the largest group of residents in the protection homes; and

Group C are those highly dependent on the staff for personal care and feeding due to their bed-ridden condition or their inability to perform self-care.

Each year about 10-15 Group A psychiatric patients in Thanyaburi Home have an opportunity to practice living their daily lives in a “little house in the Centre”, waking up, taking a shower, washing and collecting their clothes without anyone telling them to do so. But there are rules that they must obey, such as no alcohol. After this, some of them are sent to work outside according to their aptitude; some work in factories and enjoy a more independent life. Even so, they still need continuous monitoring to ensure they keep to their treatment medication. Several stopped taking their medicine and turned to drinking, losing their jobs and having to be readmitted the home again.

There are no data on the patients residing in the little house in the Home last year, but in 2017, 2016 and 2015, the numbers of residents, both patients and non-patients were 0, 16, and 5 respectively. In addition, some of them were sent to learn occupational skills, such as plastic separation, various crafts-making, on the Centre’s premises.

Most patients never come out again

“Uncle Uan will remain in the Home all his life.”, said Sittipon.

For various reasons, their psychiatric condition, low life capital, low skill levels, inadequate ability for self-care, etc., psychiatric patients do not have much chance to leave the Protection Centres. To address their problem at the cause is very difficult unless there is a mechanism for continuous care from the beginning. Sittipon offered his suggestions that the state must have in place a mechanism for taking care of psychiatric street patients which starts from rescuing them from the streets, rehabilitating them physically and mentally, training them in life skills and occupational skills and creating opportunities for resident patients in the Protection Centres. There should be facilities specifically suited to homeless psychiatric patients so that they receive appropriate treatment, can recover the lost skills necessary for living, learn new skills, and return to live in society with full potential. The Mental Health Act must protect psychiatric patients’ rights to treatment and care without being stigmatized and enable them to live productively through quality treatment, and create more awareness of mental disorders among the general public.

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”