“The NCPO’s motto is ‘Returning Happiness to the People’, but I receive only bitterness. I don’t know where my happiness is,” said a community leader arbitrarily detained because he allegedly is an 'influential person' which must be suppressed under NCPO Head Order No. 13/2016.

On the second anniversary of the coup d’état by the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), the coup-makers aim to reduce social conflict and to boost harmony among citizens.

Article 44 of the 2014 Interim Constitution of Thailand grants “the head of the NCPO” the authority “to make any order to disrupt or suppress any actions, regardless of the legislative, executive or judicial force of that order. That order, act or any performance in accordance with that order is deemed to be legal, constitutional and conclusive.”

Subsequently, there have been many orders from the head of the NCPO to promote the government’s policies under the slogan of ‘Returning Happiness to the People’. Next came the suppression of influential figures and the promotion of reconciliation in the country through NCPO Head Order No. 3/2015, which appoints military officers as peace-keeping officers. Peace-keeping officers can order any person to promptly report to the peace-keeping authorities and can detain any person for up to seven days following a summons.

Additionally, NCPO Head Order No. 13/2016 also empowers peace-keeping officers to summon any person based on stipulated criminal offences under the Criminal Code. The NCPO justified this order as a measure to suppress influential figures and to prevent political violence.

But who in the eyes of the NCPO are influential figures? Who has been detained because they are perceived to be influential figures? Are they really the local mafia? What they have been through during detention?

Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) has interviewed one person who has been summoned because he is perceived to be an “influential figure.” Anan Thongmani was one of three persons summoned under NCPO Head Order No. 3/2015. Prachatai translated the piece into English. (All photos are courtesy of Thai Lawyers for Human Rights.)

Anan Thongmani

Anan Thongmani is a resident of Paknam Subdistrict in Rayong Province. He is the president of a local community enterprise group for the Paknam coast. Anan is a community leader who demanded that Rayong Municipality call off the eviction of the coastal area where community members had been making a living. He spearheaded the submission of a petition to the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand to demand that state agencies provide a remedial plan for residents suffering adverse effects on their livelihoods from the eviction plan.

On 29 March 2016, Anan and two others were detained at the 14th Military Circle, Chonburi Province, for two days and a night. His summons sheet stipulated that the reason for the summons was under the authority of NCPO Head Order No. 3/2015 on Maintaining Public Order and National Security and NCPO Order No. 4/2016 on Addressing the Problem of Encroachment on Public Land. His actions were deemed to be those of an influential figure.

Who is Anan? Is he an influential future who can cause violence to his fellow countrymen? The following is the story of a person who has been labelled an influential figure in the NCPO’s view. The following interview leaves it to the reader to consider if he is an influential figure or not.

Who are you?

I am a fisherman. I used to own a fishing boat. Then I sold the vessel. At that time I did not know what to do so I processed seafood at the beach in Paknam Subdistrict. I inherited this occupation from my parents and my maternal grandpa. I took over the job and set up a small processing area on the beach. The processing area later expanded to a large processing shed. Finally I received an eviction and demolition order. This photo is the result of the demolition order.

Who owned the land before the eviction order?

It was an indigenous domain since my grandparents’ generation. They had been making a living on the beach where they unload the catch from their fishing boats. The beach was used as a market and primary seafood processing area for peeling cuttlefish and drying fish. It was a traditional way of seafood processing, relying on seawater, sunlight and sea breezes. They used small boats to catch fish on a small scale and family-based processing sheds. Later there were larger fishing vessels and commercial scale fishing, so people took the catch from commercial vessels to process. The enterprise has been growing steadily. There are larger companies that buy the processed products for reprocessing, so we had to expand to meet the commercial demand. In 2515, Rayong Municipality planned a beach front road.

At that time, officials brought papers for community members to sign. The villagers did not know much, so one after another, they signed the documents. Later, the municipality officials arrested community members for trespassing. Of course, the villagers contested this because the area is the usual place to unload the catches from boats and to dry fish. The Municipality decided to compromise. As a result, the villagers continued with their livelihoods until just before the eviction. Recently, there was a consultation between the villagers and the Municipality right here. There was a paper, which was similar to a gentleman’s agreement, that there would be a zone for seafood processing before an eviction. The villagers have been waiting for the processing zone.

At the present during the NCPO rule, there is a beach clearing policy. The government ordered a nationwide beach clean-up policy. People have been evicted from public land. We have to concede. Nevertheless, it would only be fair to compensate us with an area to accommodate the livelihoods of the poor at the grassroots level after the eviction. We need a place to make a living. The eviction took away our traditional occupation without any remedial measures. We are suffering. Some people cried when the army officials dragged them away from their land. What else to do? Now they are penniless.

Anan and his wife picking up the remains of their house under a demolition order.

I am here because of the Municipality Order that provides a remedy for people in the aftermath of the beach clean-up policy. I have been living and waiting for the authorities to assist me and allocate some help. I am wondering if they can tolerate seeing people who have been uprooted. Our traditional livelihoods from their grandparents’ generation have been destroyed. This is what we have been left with. My seafood drying panels have been piled up here.

Community members have been planning to organize a system and form a community enterprise, which can later be registered as a private judicial entity. However, when faced with eviction and demolition orders, everything that we have collectively built from fund-raising, deposits, and a credit union group that gave micro loans to members for their livelihoods, was demolished. Community institutions such as the crab bank, credit unions, the community enterprise, and so on. There is nothing left. If they want to see me cry, I could. We are devastated.

Before the NCPO policy to clear public land, the Municipality attempted to evict the seafood drying sheds. What was the result of the action?

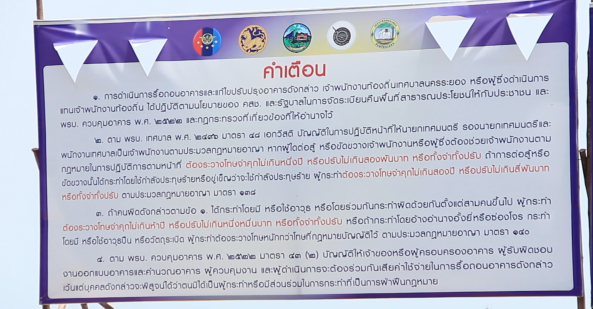

Rayong Municipality filed a petition to the court for an eviction order and the demolition of all structures. The public prosecutor however decided not to forward the issue to the court. So the Municipality used the Building Control Act to order an eviction. The Municipality said, as seen on the sign, that the structures were built without proper permission, the buildings are falling apart and the electricity cables are not up to standard, so the building can be a danger to other people.

The community decided to appeal the order to the court and requested Rayong Municipality to wait for the appeal verdict. But the Municipality posted an eviction notice. Villagers disagreed with the eviction and demolition notice as they were waiting for the verdict. At dawn on 29 March 2016, military officials invited us for coffee and took us to the 14th Military Circle. Then they ordered us to sign a Memorandum of Detention.

The accusation that I am an unwitting influential mafia figure really gets on my nerves. I would not have felt that intimidated if I was on my own, but I have a family and dependents who would starve without me. My family would be in hardship without me.

Did the army officials set any conditions before you could be released?

They said I must follow the resolution of the consultation meeting. There was an agreement from the meeting when we had a handshake and the agreement to demolish the commercial structures. I was also forbidden to be near a mass of people or to approach villagers for a meeting. I strictly follow the instructions. I even skipped a neighbour’s ordination ceremony since I do not want to be ‘invited’ by the military. I am afraid I will be in trouble because the army has told me not to do this. Now I do not go to a wedding reception or any crowded place. I follow the order because I do not want to be summoned again in the future.

Currently I am terrified of the accusation of being an unwitting Mafia or influential figure. I would not have worried if I were on my own, but my family would suffer hardship without me. My dependents would starve. My family does not have a car. As a husband, if I am arrested, I don’t know if my wife can ride a motorbike. If I’m not there, she can’t go anywhere. If my kids do not know my whereabouts, they will not go to school. I am a father and a grandparent, so if the military arrest and detain me, the family will be dysfunctional. I am not really afraid of my fate but I really worry that the family will be disrupted and break down without me.

Anan’s temporary shelter for his family. On the far right are the remains of his former house.

Why did you decide not to lodge a complaint with human rights organizations [the National Human Right Commission of Thailand] this time, when you filed complaints earlier?

In the past I felt we had some channels to push our issues to Parliament and through an elected government where we can raise our grievances and petition to delay or to stop a programme that may affect community members. We used the channels, and government officials, Members of Parliament or Senators would conduct a fact-finding mission or even provide primary assistance. Other agencies and organizations also paid attention to the problems in the area, so it was a relief for us. However, currently everything depends on the NCPO head’s orders.

I only wish that there was some budget to support relocation or that there was an agency to provide assistance for people’s livelihoods along the coast to make a living. I feel that everything is constricted and that I cannot find any room to breathe. It is impossible to find space. I am wondering why the government only helps the rich who receive concessions from land reclamation. They can extend their area up to ten kilometres from the shore and open large plants. But the native population living along the shoreline for generations have been victimized and evicted from the beach. The officials used machines to demolish our houses and structures.

At present no remedial measures are available. Could you please tell them and enlighten them of the differences [between the rich and the poor]? As you can see, the land reclamation extends from the shoreline for ten kilometres and the practice is legal, whereas the villagers living along the beach who have been trying to make ends meet are illegal. Is this the life we have to live these days? Is this justice? Do they have any justice for coastal communities who rely on the beach for a living? Can they be fair to us?

After your arbitrary detention at the 14th Military Circle, because the military officials thought that you were an influential figure, do you view yourself as an enemy of the NCPO?

Not at all. I don’t think I am adversarial toward them. I never thought that I would violate any NCPO order. The NCPO’s motto is ‘Returning Happiness to the People,’ but for me, the NCPO only returns bitterness. I don’t know where my happiness is. Unlike their motto, I am always suffering.

Anan’s current residence

Have you changed your attitude, after your detention and the “attitude adjustment” programme, and how?

The programme has changed my attitude because I have to comply with the NCPO order. Whatever the NCPO tells me or orders me, I have to follow the order, even if it causes trouble on my side. I have to respect the authority under Article 44 of the Interim Constitution 2014.

Even if the villagers’ situation deteriorates?

What else could I do? Are there any agencies that can help? Which agency can intervene or assist us? Are there any authorities that can guide us what to do to be happy? Most ignore our suffering. We have been ignored by the authorities. No one helps us. Not a single one. I have lost confidence. I am alienated and alone. I feel this group of people have been forsaken.

A sign with the Rayong Municipality Order, citing the NCPO and government policies.