Since 2006, Thailand has been plagued with an unending storm of political conflict. Political thought is divided on nearly every single issue; from former Prime Minister Thaksin’s reign, the monarchical institution, nation development, democracy, elections, reform, politicians, political parties and so forth.

The 22 May 2014 coup has exacerbated Thailand’s political situation. Activists, politicians, and even ordinary citizens branded as “ideologically hardcore” were left with no choice but to flee the country in self-imposed exile. A year later, any perceived improvement in the situation is essentially superficial; these political exiles still cannot return home. What were their reasons for fleeing? Was it because their ideologies conflicted with the current government? What are their living conditions as exiles? We take this opportunity to provide an in-depth look at how our fellow countrymen are surviving and their fate as the “Other.”

Although there is no exact figure for the political exiles who have fled after the 2014 junta, a pre-junta exile source estimate the number to be significantly higher than the 10 well-known exiles who have made international media headlines.

Political exiles include a wide demographic range, encompassing academics, activists, poets, artists, intelligentsia, and any others who have demonstrated disapproval of the role of the monarchy, albeit at varying levels. Of the political exiles, one of the groups is a small one that has been involved with a weapons case, another is part of the old guard of political rallies who are concerned about their safety, and yet others are core leaders of local groups These political exiles faced arbitrary detention and interrogation, arrest, harassment and constant surveillance to the extent where they believed exile was the safest, freest option. Even ordinary citizens who have posted an emotional Facebook status on a whim have consequently been “witch-hunted” and have been summoned by the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO).

Why exile?

For those who recall, the current post-junta atmosphere is exceedingly more oppressive and fatal than the 2006 junta. Right after last year’s junta took control, radio and TV channels were forced-shut for days. Military troops occupied street corners. The NCPO repeatedly televised a lists of people ordered to report in. Most concerning was that no one was aware of their fate once they turned themselves in. Would they be held somewhere before being slapped with a charge? The people waited with bated breath for seven days for the martial law to come into effect, and to see what would happen to the lucky winners of the NCPO “jackpot.”

Only one year has passed, and many are already desensitized to the idea of “attitude adjustments,” the arbitrary detention and interrogation of people of interest by the NCPO. Immediately following the coup, perilous uncertainty prompted many exiles to flee the country, despite having not committed any illegal offenses and having no charges or cases brought against them. Some of the political exiles’ attitudes towards fleeing were “escaping in order to fight back better.” They felt the current junta had no lawful authority to summon them without credible charges for committing illegal crimes.

“I do not believe they have the authority to summon me, and I have no reason to believe that they will proceed with me as if I am a citizen in a democratic system,” Nithiwat Wannasiri, activist and singer of Faiyen, a red-shirt pop band, revealed his viewpoint after having been exiled for a year. Nithiwat’s band sings critical, satirical songs relating to the monarchical institute and the social norms of Thai society.

“Some summoned people have been charged with Article 112 [lèse-majesté law], but others have not. Their only infraction was not appearing when summoned, and get suspended jail term. I’ve also thought about returning just to get all this over with. When the time is right, I’ll definitely return, but now is not the time. That’s because not only am I charged with not appearing when summoned, I also have a string of other cases, such as violating the martial law on 23 May when I went out and protested against the junta in front of the BACC [Bangkok Arts and Culture Center, Siam Square, Bangkok]. Even before that, Wiput (screenname “I Pad”) filed police complaints for three cases of 112 and breaking the Computer Code Act against me. Wiput definitely wants to do whatever he can to jail me. I am willing to fight for myself in these cases, but only in a civilian court—not a military one,” said Nithiwat determinedly.

Other political exiles, however, have fled the country due to unbearable conditions they have faced in the country.

Thantawut Taweewarodomkul or “Num Red Non,” an ex-lèse-majesté convict who was jailed for three years and a single father, talks to us about his experiences. After he was released from jail, he tried to resume a normal life until the coup interrupted it before long, summoning him through the televised NCPO address.

“After I was released from jail, I did not participate in anything subversive. Before going in jail, I was part of a lot of networks, so the authorities were probably afraid of me resuming my activities. But I didn’t, because I was angry at my former comrades who did not take care of me when I fell on hard times,” said the ex-lèse-majesté convict.

The political situation caused Thantawut to lose faith in the judicial processes of the state.

In 2010, a horde of police officers and reporters swarmed his condo to arrest him. His ten-year-old son was with him at the time. The authorities directed psychologically-charged questions at him and his son. Thantawut received a 13-year jail term. He was granted a royal pardon after serving three years behind bars.

“It was really hard to get through the pressure-filled time in my life. Even in prison, I was attacked and beaten up three times. I wouldn’t be able to bear going back to that sort of situation, not even for a second.”

“So after they summoned me, I had no way of knowing how long they would hold me for. But I already knew that I couldn’t bear one more day of it. I don’t know how to say it; but I just flat-out refused that possibility. I couldn’t take it anymore. I had no confidence that there was any element of justice in the junta, or if any processes or organizations could help me,” said Thantawut.

Still other political exiles—from good families who are educated, well-mannered and only exercise political views academically—have also elected self-imposed exile.

“He’s a DJ who brings up academic issues in ways that make locals understand them. He is never extremist or uncouth in his behavior or speech. He speaks logically and with reason, explaining people’s rights. That’s all. And he got a fan following from doing those things!” explained the friend of a political exile. This outlander is an ex-DJ who held a political radio talk show for a community in Chiang Mai. During the period of extreme political divisions just before the coup, another radio host also in Chiang Mai with opposing political views reported him to the police. This incident caused the ex-DJ to feel uncertain about his safety and future in the country following the coup, and he decided to leave.

“I wanted to use my skills to do my own brand of political fighting. I wanted to talk to people on a level both of us could understand by clearing up political issues, such as those regarding government and democracy. Some people were filled with rage after 2010 and wanted to take up arms. But that’s not the way. I wanted to talk to villagers in a dialogue, not to lecture them like a professor, since that’s on a different level. I believed that among 60 million Thais, there would be some people who I could talk to. And that is my way of fighting,” said the ex-DJ.

“Even if Thaksin came back and became the PM again, and the red-shirts continue to be unaccepting of differences in political opinion, then that’s still not democracy. In truth, I can’t see how the Democrat Party are going to campaign either. The conflict has escalated to the point where I think the only way is for a new generation to come in, a generation that is more accepting, so that a true democracy can be ushered in,” he analyzed.

The fate of political exiles can affect anyone from the most “extreme” activist, to more tempered mediators who critique their own sides, and bystanders unrelated to political activism but who had been dragged into banishment—unfortunately the ex-DJ’s wife.

It is difficult to say which is worse: taking your spouse with you to a life of uncertainty in forced escape, or leaving behind loved ones in favor of solitary expulsion.

A political exile

New paths in a new land

Living overseas is a challenging hardship to bear, but it’s further complicated when one has to do so without refugee status and is laden with economic as well as psychological burdens.

Typically, political exiles are not overly affluent. At most, an exile could come from a normal middle-class family who is able to send some money to support them, but this is a rare case.

The exiles we were able to contact have largely passed through the rough transitioning period after a year of banishment, and are able to find different ways to make a living.

Some émigrés have ceased all political activity, especially hosting political radio shows, out of deference to their new countries of residence. Those who believe they are not likely to return to Thailand in the near future have sought out means to make a living, as well as seek ways to help support other refugees who may follow. Exiles have opened small businesses such as selling made-to-order food (e.g. grilled chicken, satay pork, etc.), running hair salons or other various service delivery professions.. The road to opening these businesses in their new countries have been arduous; many had to work in modest occupations such as sale assistants or tour guides in order to afford the rent to open their own shops. While some exiles have been fortunate in their business ventures others have not been as fortunate. Although one exile’s opening of a restaurant has become successful enough to expand to multiple branches another exile is barely making ends meet at their failing hair salon.

Some exiles with special skills are able to find specialized jobs in designing, teaching music or other skills based occupations, egregiously they earn far less than they would in Thailand. One creative director for advertising reported that his current earnings were ten times less than the income he would’ve earned in Thailand. The exile who currently works as a music teacher for school children on weekends earns 2,000 baht a month, incomparable to his 100,000 baht monthly salary he had working for a large company in Thailand.

We were able to interview one exile who flourished under his circumstances. In Thailand, he had a strong background in the civil society sector before becoming a communication specialist for a Thai politician, which made him a political target after the junta took power. After he fled Thailand, the gravity of his situation took a significant toll on his emotional state which caused him to suffer from a deep depression that mentally paralyzed him for four months before he was able to move forward. He was able to rise above adversity and went on to build an agricultural business network through renting out agricultural land which earned him millions of baht.

“If we can’t even feed ourselves, then how are we going to fight back?” said the young entrepreneur. He went on to discuss his new venture that would help support other political refugees living in poverty.

Exile Productions, Inc.

Yet there are also political exiles who remain active, broadcasting political videos on Youtube that we cannot discuss here since they may be illegal in Thailand. Nevertheless, a dialogue with these exiles is useful for political insight and development.

The political talk shows vary widely on the political scale: from village-style extremist to ideology-laden intelligentsia stances.

The hosts of one of these shows stated that their shows emphasize dissemination of information rather than scathing rhetoric. They want to discuss issues they see as creating problems for Thai society. While these shows are widely opinion based, it is vital for democratic societies to have an open space for dialogue, debate and exchanges of ideas., Thailand does not offer any chance or space for these hosts or other citizens to openly and logically discuss varying political views.

“We had to leave the country because the [political] situation forced us out. We didn’t want to leave. But now that we have, we need to make the most of this opportunity, so the people in Thailand can know that we still exist, we are still fighting,” said one exile.

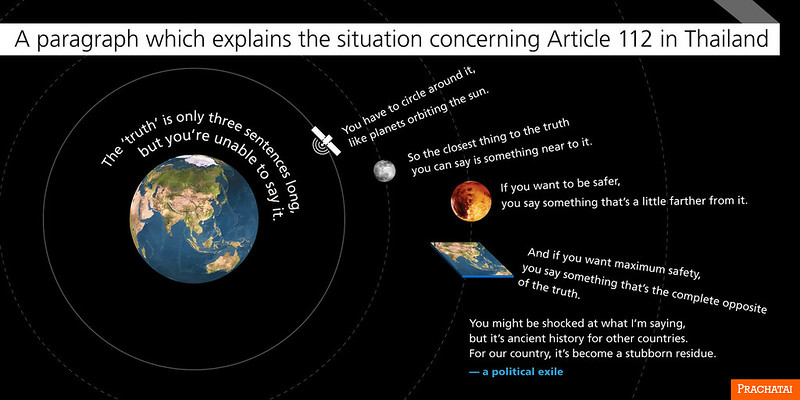

“‘The truth’ is only three sentences long, but you’re unable to say it. You have to circle around it, like planets orbiting the solar system. So the closest thing to the truth you can say is something near to it. If you want to be safer, you say something that’s a little farther from it. And if you want to have maximum safety, you say something that’s the complete opposite of the truth. You might be shocked at what I’m saying, but it’s ancient history for other countries. For our country, it’s become a stubborn residue,” said an elderly man who is a first-generation refugee who fled after the 2006 coup.

The elderly man does not agree with the political talk shows hosted by the newcomer exiles who often take no care in using hate speech against the opposition political figures. However, he does not attack or prevent the newcomer exiles rom producing these shows, preferring unity over division as well as holding to their ideals of freedom of speech and believing that the audience are able to decide for themselves what to watch and believe.

He poignantly commented on the younger exiles, “Like us, you also believe in human rights, so although we don’t think these political shows are completely correct, it’s also a matter of taste. Some people like to eat koi dib [a raw meat salad]. But others will never eat it, even if it’s prepared completely up to health code standards. The person who’s eating has a choice of what they want to eat, so even if I never eat koi dib I have no right to condemn another who loves koi dib.”

In response to this, a young exile said he disagrees with the old man. It should be noted that the older exile and him have major differences in political views, especially those concerning Thaksin Shinawatra, the ousted ex-Prime Minister. They argued continuously, with no regard for age differences.

“If we hold to standards of freedom of speech, then we can investigate, criticize, even revile public figures, including Thaksin.” The young exile said, expressing his views that “reviling” public figures will help to revolutionize public thought toward political figures, imbuing ideas of equality within the audience.

“Even though I don’t agree with them, I still have to protect their right to express themselves,” he said.

These ideas, especially their usefulness towards progressing Thai society, are debatable from both sides.

At the edge of the beyond

Other than the exiles that are activists, artists, intelligentsia, or ex-Old Guards, there are also exiles that live in abject poverty and are completely without fame. We are not sure of their political stances since we could not make contact with them. They live in tents on the fields of obscure farmland, and are unable to find jobs since they do not have specialized skills. Most of these abject exiles are from the lower class who already suffered in Thailand, and suffer even more so in exile. Most of them are red shirts accused of illegal possession of weapons.

The feet of some exiles

The heart of an exile

We started investigating about the exile experience after many had already gone through a painful and grueling transition phase and had, to some extent, settled down. Therefore, most exiles were not willing to tell us extensively about their harrowing journey but we caught some horrific glimpses. Immediately after exile, some had recurring nightmares, while others lost the will to live. Some refused to learn the local language in their new country, prolonging the adjustment process and miring them in depression. Some suffered from severe anxiety to the extent that it metamorphosed into physical conditions, such as panic attacks and literally being paralyzed with fear, requiring them to seek medical attention.

“I didn’t have much trouble adjusting, since usually I’m introverted and I like to travel. But when I was first exiled here I had recurring nightmares that woke me up every time. It was unbelievable,” said one exile. He was a middle-level office employee who worked in the ad industry. He had to leave the country before the 2014 coup for many years because he was on a political web forum fanclub. On that web forum, he enjoyed exchanging political debates and discussions in an intellectual, logical but straightforward manner, but never in an defamatory or uncivil way, he said.

“Whenever I see injustice, I can’t help but say something, since I’m a straightforward person. Especially when I get mad, I get even more straightforward. Actually, the case against me hasn’t progressed far at all. If I kept quiet it wouldn’t be hard for me to stay in Thailand. But I know myself well, and I wouldn’t be able to keep quiet at all, so I decided to self-exile. I couldn’t bear it if I went to jail, even for just one day,” said the ex-commercial maker.

The youngest political exile we encountered was 19 years old. He left his post as a first-year university student since he was unsure whether he would be hit with a case against him. This young exile said that he did not have strong political views, but enjoys artistic activities and has an interest in sociology. A senior at the university invited him to participate in staging a play, an amateur production. He played a character that stared in just a few scenes which totaled less than 10 minutes but would go on to his life forever.

His two seniors were arrested and sentenced to two years and six months in jail. He and the other participants in the play, noted in the arrest form as “those who we could not detain yet,” escaped into exile. This 19 year old is an orphan who had been living with his relatives, so exile seemed like the only option for the confused young man. He said that he is not an activist, not an intellectual, and didn’t even have political goals. No matter how long time passes in exile, for him there is only depression and the question, “why?”

“I feel so sorry about the loss of my future. I was only 18 when I had to escape. My entire life ahead of me... ” he paused for a long time. “I regret everything. I guess being in jail would be worse, but even without a clear case against me, being in Thailand would be worse too. But here, I’m afraid to go out anywhere, because there is only fear.”

“I help some of the other exiles with their political talk shows. At first, I didn’t think I would come here and do anything like this. I had 10,000 baht with me when I escaped. I had 2,000 left after two months. How was I supposed to live? There was no way to make a living. Then another young person escaped too, and we started making a show just for fun. Then some listeners started donating money for our daily expenses. Usually I’m not vocal about these issues, but now I have no choice but to speak.”

“I didn’t choose this fate for myself. Everything I did was because it was necessary, I didn’t choose it. Someone pleaded for me to participate in the play. I had no choice but to self-exile or be jailed. If I don’t do this radio talk show, then I would starve to death,” said the young man.

Is a refugee status impossible?

Many exiles are hoping for an official refugee status from the UNHCR so that they are able to live in a different country, although this is a very difficult endeavor. The process is lengthy and few are ever taken into consideration. The young exile wants to study abroad in a developed country, but this seems unlikely. The advertising executive dreams about making a documentary about Thailand’s lèse-majesté law to communicate with apolitical Thais, but to do this he needs an official refugee status. He went through all of the necessary paperwork procedures but was finally rejected.

“I submitted my application as a regular citizen, not as an activist or an academic. You see: normal person does not get rights or protection,” said the ad executive.

The ex-DJ from Chiang Mai had also hoped to obtain a refugee status in order to settle down and make a better living. He has researched for solutions but came up empty and deadlocked: unable to go back or move forward.

“If I went back now, like a lot of people, I would have to live in constant fear. Even if there was an amnesty law, I may be able to work and live my life, but still if there still is Article 112, one day they could arrest me. How am I supposed to live under that law? How can I be sure of the stability of my own life?”

“Living here long-term is unsustainable. I want to live somewhere else. Honestly, some people [exiles] who get to live in developed countries and share pictures on social media are very inconsiderate. There are so many people who are unable to go anywhere, and the people who are able to share mocking posts that discourage exiles,” said the ex-DJ.

As for Thantawut, the single father, he has decided to settle down and make a living in his new home, a path he finds more honorable than living off of donations. Settling down and supporting himself is a necessity so that he can bring over and support his son. Currently, his son is living with guardians in Thailand who plan to stop supporting the boy when he finishes junior high school in the next few months.

“If I can’t settle down here, then I’m out of options,” he said, eyes full of unanswerable questions.

Wounds and hopes

“If I went back to Thailand, I would have to begin at square one. If they let me live my life there, I could probably run a business there and survived. People who used to be in jail are afraid of going back there. But because “you” pushed me into this exile position, because “you” are targeting one little citizen, because “you” framed me that I’m a key person in a political movement, according to a leaked secret document. If given the chance, people like me could do a lot of good for my country,” Thantawut said passionately.

“This predicament have been supposed to be over. Now, however, I’m only thinking of death. My father will soon die, and then my mother. I feel like I don’t have enough time to build a new family; my life is ending soon. All I wanted is to take care of children and have someone by my side. When I was put in jail, my son Web was only 10. I was released when he was 13. He was already a teenager. I want my 3 years back to spend with him, but it’s impossible. He’s as large as a buffalo now. I can’t kiss his hair or smell his feet now; it’s not the same,” said the single father.

One of the largest things for exiles to deal with is the death of relatives.

“The most painful part of exile? That’s hard to say; lots of things are in the running. But one of the worst parts for me is when my mother had a car accident when her car fell into a sandpit 30 meters high. All I could do was hear about it. I couldn’t go to visit or see her. Not only that are the countless deaths of my other relatives and friends; I couldn’t attend their funerals or see my loved ones,” said Nithiwat.

He continued, “Of course I want to go back. It’s my home. My family, friends, all of my memories are there. Everything is back there. Songs like “Missing Home (Full Moon)” and “Cry from the Motherland” were inspired by homesick emotions of me and other refugees in exile from tyranny.”

As for older political exiles who have escaped since the 2006 coup due to lèse-majesté cases, we asked them about their expenses.

“I have both expenses and income. I’m not telling everyone to live like I do. But I’m at the age where I can afford to be a political exile. I’ve taken responsibility for my family. I also have money saved up. Some people save up money their entire lives and never get to spend it. I’m lucky that I get the chance to spend every single baht I’ve saved. This is the most valuable time of my life. I’m being forced to travel, since I can’t stay in one place for too long. How cool is that?!” said an elderly exile, smiling.

“I have to thank them for forcing me to choose, or rather, giving me no choice but exile. To me, the issues plaguing Thailand are really small issues, easily discussable. Think of Black May before folding. Think of 66/23 [an order issued in 1980 by the then-PM Prem Tinsulanonda to eliminate Communist insurgencies]. Murderers were given the chance to continue developing Thailand, were given a hundred or two hundred thousand apiece. And what’s happening now? Normal people are jailed for half a century. This is madness.”