The Deep South peace process often focuses on the Muslim Malay, but there are several other minorities that do not have much of a voice in this process. Prachatai talks with a Buddhist Thai group, an LGBT group, and ethnic Chinese on their views on the regional unrest.

The conflict in Patani, or the three southernmost provinces, draws most attention to Muslim Malays, since their unique culture and identity has long been oppressed by the Thai state’s assimilation policies. Muslim Malays in Patani have also had their human rights violated by the state: from 2007 to 2013, the Muslim Attorney Centre Foundation received 3,456 complaints of human rights abuses from the Deep South. Most of these complaints involved Muslim Malays and allegations of enforced disappearances and torture in detention by state officials under the emergency decree and martial law. Muslim Malays’ everyday lives are also rife with discrimination by the state: they are stopped and searched at checkpoints, and DNA samples are arbitrarily taken and recorded by the security authorities.

In the past couple of years, the Thai state has been relaxing its policies in the Deep South, allowing a more open space for the expression of Malay culture and identity. The state has seemed to understand that giving a cultural space to Malays is one step towards a compromise for peace in the region. Not only that, the peace process has given importance to the needs of the Muslim Malays.

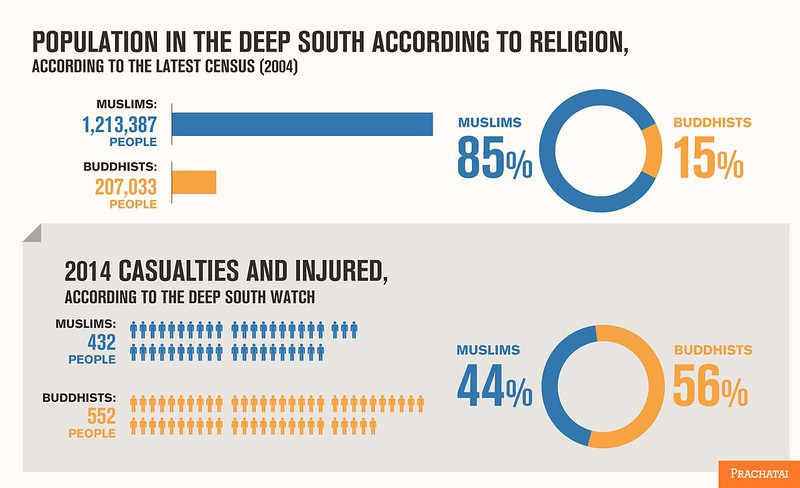

Still, Muslim Malays are not the only group to be affected by the violence: ethnic Thais, ethnic Chinese, and other groups are also similarly upset. The interesting thing is, although there are six times as many Muslims as there are Buddhists, the casualties from the violence affect both groups in about equal numbers.

The

statistics from Deep South Watch (DSW) for 2014 show that the number of Buddhists (including Buddhist civilians and officials, both Thai and non-Thai Buddhists) who were injured and killed in violent incidents were greater than Muslims (Malay and non-Malay civilians and officials included). From the total number of 993 dead, 432, or 43.5 per cent were Muslims. Buddhist casualties numbered 552, or 55.6 per cent. However, Buddhist and Muslim figures were not categorized into civilians and officials. (Insurgency incidents as defined by the DSW include deaths from: car bombs, ambush attacks, attacks with or without weapons, surrounding cars, arson, and discovery of corpses.)

The Deep South’s elite, especially elite Malays, and academics have a large role in the ongoing peace process. Minorities, however, do not have much voice —even though they are also Patani locals.

Prachatai interviewed Rukchart Suwan, a Buddhist Thai from Yala province and leader of the Network of Buddhists for Peace, Anticha Saengchai, an LGBT activist in Pattani province, and an ethnic Chinese living in Patani who asked not to be named, about their lives as minorities in Patani, and their thoughts on the peace process.

Rukchart Suwan

Leader of the Network of Buddhists for Peace from Yala

“Two years ago, I participated in a peace process seminar. I met people who used the words ‘Thai state’ and ‘Patani,’ and I felt shocked and confused. I was uncomfortable with these terms. After learning more about them, though, I had to accept them as part of the painful history of the people here.”

“The first time I heard the historical narrative of Patani, I thought it was completely crazy. That’s because since I was little I had only known the nationalist version of Thai history. They were talking about ‘Siamese colonialism’; I was very confused. Why didn’t they talk about Thais fighting against Burma and France instead? But these weren’t part of Patani history. I thought they were focusing too much on the painful part of history, when there were also joyful parts as well.”

“Around the end of 2013, I set up a small group of Buddhists. At that time, Buddhists were being attacked a lot. We gathered to discuss and vent our anger, frustrations, and sadness. We didn’t dare express these views publicly, or to any non-Buddhists. Then a Buddhist kid got shot, his brains flowing all over the teahouse, I felt like I had to stand up and do something. I printed flyers to denounce the act and distributed them at the teashop. The killing at the teahouse built a strong momentum, and even shook the higher-ups’ discussion tables. We wanted to say that violence shouldn’t happen to either Thai or Muslim soft targets, both are uninvolved parties.

“We named the group “Minority Buddhists Group,” since we wanted to communicate strongly to the state the fact that we are a minority. We also wanted Buddhists to realize and accept the fact that we are a minority, and have to live with being the minority in a minority. But there were many people in the region who felt that this name was too extreme, so we changed the name to Network of Buddhists for Peace (B4P).”

“We set up the network so that we Buddhists can have a space to participate in the peace process. In the past, we’ve been a very quiet group, too scared to express political opinions. Whenever the state discusses peace talks, they go and discuss with only Muslims. This network was set up so that we could be heard, too. Then, we started holding activities to inform local Buddhists about their rights and the peace process, because compared to our Muslim brothers and sisters, we aren’t as informed about political processes. In addition, most Buddhists are quite narrow-minded, viewing all Muslims as bandits. They don’t open up their hearts and minds at all.”

Soldiers come in, community shatters

“We were working on our community, just minding our own business when the soldiers came in and ruined everything. Boom! Everyone became more divided than ever. Having a military presence in the community made Buddhists and Muslims even more suspicious of each other.”

“The soldiers take people for training and order us around, which weakens our sense of being civilians. Whenever there’s an incident, they tell us to go there and do that, which isn’t even our job. It gets to the point where this community has been called a militia village.”

“The authorities have got money from proposing projects with our community, but we don’t benefit from those projects at all. I want to ask them: you came to be a government official down here, do you even love this area?”

“The Buddhists here have received very little positive action from the state. When the state solves problems, they look to our Muslim brothers and sisters first, like they’re saying that they have to take care of Muslims first, Buddhists later. This is a wrong way to go about solving problems.”

“To solve conflicts, there has to be an approach of equality. For example, the extra care taken towards Muslim youth. It’s not like they never pass entrance exams; many pass to enter the medical, nursing, military, and police institutions. Muslims and Buddhists get the same amount of education, so I think that there’s enough rights and favouritism given already.”

“I think the peace process shouldn’t include only Muslims, or Buddhists from the Central region of the country. It should include Buddhists in the three provinces as well.”

Prejudices between Buddhists and Muslims

“This past Ramadan, the situation seemed peaceful until a Buddhist teacher was shot. The Buddhist community responded with a feeling of ‘here we go again.’ Everyone started sharing ISIS decapitation clips but saying that it was a video of Deep South Muslims cutting heads off of Thai soldiers. I had to clear this up with Buddhists, who were venting very harshly. I had to mediate and calm them down.”

“Buddhists here are prejudiced against our Muslim brothers and sisters, often generalizing all of them as ‘bandits.’ I try to explain to them that we shouldn’t generalize about Muslims, since not all Buddhists are good people either.”

“We have Muslim friends, but we don’t talk to them about the insurgency or peace. Buddhists here are too afraid to discuss these topics with people they don’t trust. But if they’re with other Buddhists, then they vent full speed, using words full of prejudice, due to close-mindedness and ignorance.”

Buddhists want a role in the peace process

“Buddhists here are largely unaware of the political situation in the Deep South, but very aware of that of the capital. Buddhists here are very active supporters of the PDRC (People’s Democratic Reform Committee), even travelling all the way to Bangkok to protest. But when it comes to the local situation, they cower and keep silent. For example, if there’s a public stage about Deep South issues and a hundred Buddhists attend, not one of them will let you photograph them. They’re afraid that if their photo is leaked to the press, then they could become a potential target of violence from ‘them’. Actually, I’m afraid of being targeted too, but I have to face my fears.”

“One of the reasons Buddhists here turn to the PDRC is because they blame the violence here on Thaksin, especially when he came here and talked about the ‘500 baht bandits.’”

“Buddhists here are devoted to the ideologies of the Thai State: Nation, Religion, King. They love the monarchy and feel more tied to the nation as part of their identity much more than being a Deep South local.”

“A lot of Buddhists have moved out. Twenty families in this community (Baan Kuha Mook) have moved out in the past decade. A lot of other families have moved out to be with their children studying in Bangkok. But I’m not moving out. I was born here. I’m tied to this place. Especially as a leader, I can’t just escape.”

“Buddhists here think that their politics is the national politics, not regional. Having no demonstrations and protests at all is a good thing. We hope that the military junta will improve the situation in the Deep South. We think they will do a better job than an elected government because the military is the real one, so there should be a more tangible progress. We have huge hopes for the soldiers to fix problems here.”

“Don’t hurt me!”: the most basic request

“The thought of living in an autonomous territory, much less a sovereign state, has never entered the minds of Buddhists here, since we all assume that whatever happens, nothing will change.”

“Buddhists haven’t ever thought of any demands yet. We just want the situation to end as quickly as possible so we can get on with our lives peacefully. Buddhists are interested in the peace talks to make the situation end, but virtually nobody is interested in setting up a political organization.”

“I think that no matter the outcome, it is all OK if we are able to coexist. I also want a clearer picture of how we Buddhists will live, and what political role we will have. I’m scared that if the Muslims govern, Buddhists will be persecuted. What if they infringe on our culture? Will they set up cultural boundaries? For example, there was recently a Buddhist festival in Yala called the City-Gods Festival. If there’s a Muslim in charge, will they allow us to have this festival? We have a lot of questions about how we will be taken care of.”

To the Thai state and the independence movement

“We urge you to stop harming soft targets. We are not your opponents in any way. Repeated acts of violence make us fearful. If the independence movement is serious about the peace process, then the political wing (who engage with the peace process) should tell the military wing to cease all violence towards soft targets.”

“We want the state to continue holding peace talks, especially open ones. They can continue having secret talks, but there should be some that are open to the public too, so locals can feel included. Holding only secret talks will create an atmosphere of ambiguity and confusion.”

“If MARA (MARA Patani is an umbrella organization of the insurgency movement, which has just started talks with the Thai state) wants to come talk to me, I would be very willing to do so. They seem interested in our lives. Communication between us would clear some things up. However, most Buddhists are still holding onto their prejudices, which will be hard to change. If MARA asks us what our first and foremost request is, it would be ‘don’t hurt me.’ We need a guarantee for the safety of Buddhists here.”

“I still have hopes in these peace talks, which seem more tangible and clear than the ones before, even with the release of the

BRN clips (Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) is a militant Islamic insurgency group active in the region). I hope that the talks will continue. In fact, I feel like attacks on soft targets have lessened a lot since the talks started.”

Anticha Saengchai

LGBT activist, philosophy lecturer at Prince of Songkla University (PSU), Pattani campus, and owner of Buku Books & More Pattani bookstore

“I became a philosophy lecturer at PSU Pattani and then opened Buku bookstore around the end of 2011. I opened a bookstore because when I was in Chiang Mai, I was impressed with the little bookstores there that were full of the books I liked. I don’t like those big bookstores, since they’re full of books I don’t like, and books are hard to locate. Pla (Daranee Tongsiri) also ran a bookstore before, so she invited me down here in Pattani to run a bookstore.”

“At first I wasn’t used to the culture here at all, but I kept on going because I wanted to get to know the culture here. As time went on, running the bookstore got me to mingle with the people here and I got to know them better.”

“At first we didn’t make clear what our relationship was. Later, when we made it clear we were an LGBT couple, it helped to filter the people who came to work and interact with us. People who came up to us were people who understood and accepted us, and that made working easier. People who weren’t okay with us just stayed away.”

LGBT in the Deep South: the elephant in the room

“When we outed ourselves, Buku became a meeting place for Muslim LGBT, with many coming out to us at our bookstore, asking us for advice. We listen to them, because finding a safe space to speak about these issues is very hard to find here.”

“Then we started holding gender classes, a small discussion group of no more than 10 people. The people who came to discuss included straights, LGBT, and family members of LGBT people.”

“Our gender-oriented activities did come into conflict with some Malay Muslim activists. They see that this issue is not so important, and don’t want to know about it or get involved at all. Some don’t agree with us talking about these issues out in the open. Usually, it’s a lot less trouble to discuss women’s issues than it is to discuss LGBT issues.”

“For example, if we were to say that ‘this area has problematic issues with the treatment of women’ then we would get a response saying that we are outsiders, and can’t understand the people here. But that’s exactly the problem. Gender issues are a very big issue in the Deep South, but there’s resistance in discussing these issues, and people are too afraid to discuss them here. It shows that this is a serious problem here, although not at a vicious, venomous level. I see a lot of Malay Muslim youth activists who are open to gender issues, but they have no power to discuss them or are too afraid to do so because they would be met with resistance from the community.”

“I feel like the men here are afraid of losing their authority and leadership, and believe that women’s authority lies in the kitchen, and in supporting their husband to become leaders. Most women subscribe to these views and do not raise issue with them. Sometimes, women suppress other women among them from raising the issue. The idea that a good woman is a woman who supports the man in becoming a leader is a very deeply embedded one.”

“Women here are largely unable to speak out about their problems. If they do, it’s mostly career-related problems, and jobs that are open to women. They won’t discuss structural issues that are oppressing women, such as institutional, social, cultural, ideological, customary, or religious ones.”

Unlocking the gender issues with common humanity

Daranee Tongsiri (Pla) and Anticha Saengchai

“It’s very hard to get Muslim Malays to understand LGBT issues. They’re attached to their religious framework that views LGBT as sin. So when we try to bring up this issue, we start by saying that we’re not going to look at religion, but we will look at the basis that everyone is human. We say that LGBT people are human too, not just sin. We tell them to look at LGBT from a new perspective: fine, you can view it as sin if you want, but we can still coexist and be friends.”

“Some people are anti-human rights altogether, saying that it’s a Western import that will draw people away from religion. But we found that many human rights do not come into conflict with Islam at all, only with the customs and mores of the people here.”

“Many people, when talking about violence by the state, will refer to universal standards of human rights, governance, and individual autonomy. They will call for intervention from organizations such as the UN and OIC. But when it comes to women’s and gender issues, they say ‘don’t take in international standards’.”

“If Islamic law was implemented here, what do you think will happen? Just look at Aceh. If that happens we’ll probably stop working on gender issues here, or even move out altogether, since it won’t be safe for us.”

“Nevertheless, we do not believe that Islam is an obstacle to understanding human rights and gender issues. The problem is with the interpretation of religion. In other countries, we see many Muslims campaigning for women’s and LGBT rights. There’s even a gay pride parade in Turkey. There’s a Muslim Feminist movement in Malaysia. And they still follow the Quran. We see these groups all over the world, but not in Patani. So, Islam is not the problem in understanding human rights, but the issue is with the customs here that construct an ideological ceiling. The society here builds upon and emphasizes masculinity very heavily, mixing these mores with Islamic ones.”

The elite-only peace process

“We feel like it’s a very elite process. They don’t involve regular locals or take them into account. Elites just assume for themselves what is fitting for the people here.”

“We want the peace process to involve more diverse people, giving space to women’s and LGBT issues, as well as space for other minorities to voice their concerns. At the moment, minorities have absolutely no voice in the process, which seems to be just political shows and acrobatics to maintain power in the hands of the current elites.

An ethnic Chinese man, who asked not to be named, around 60 years of age and a Christian

“I’m a Hakka Chinese. My mother doesn’t even know exactly how many generations her family’s been here, but we have been here for many. My father was born in China and immigrated here. My clan’s foundational house was elsewhere, but during World War II the Japanese came into [the Deep South] and oppressed the Chinese, and many escaped to live here (Muang District, Pattani Province).”

“My mother’s side of the family has passed on many stories through the generations. One of them is of a Patanian princess riding up to us on a horse. We don’t know the princess’ name though, because Chinese here aren’t really interested in politics.”

“The Chinese brought in technical knowledge such as making glasses, tailoring, and farming vegetables. When Malay people are getting ready to go to Mecca they would come to Chinese tailors to get their pilgrimage clothes made. At present, pretty much all the gold shops and pharmacies are run by Chinese people.”

“Speaking the same language as them helps the Malay feel at ease. When I sell stuff, I almost never use Thai.”

“Local people get along best with Chinese people, since we can speak Malay, unlike the Siamese. The Chinese people’s defining characteristic is being able to assimilate and adapt to wherever we go to live, and not cause divisions or conflicts. Chinese people are focused on commerce and not politics, and our habit of assimilating comes in really handy for this.”

“Chinese people view that we shouldn’t get in trouble with local people, but assimilate with them instead. We aren’t concerned that we’re losing our identity or anything; it’s a natural part of living in a community.”

“My family hasn’t thought about moving out. We fit in well here and we don’t have much anyway. We feel safe and okay in the city, but other Chinese brothers and sisters living out in the more rural areas feel like they are potential targets for violence, since they have been affected. Although my family and I get along well with the locals here, we can’t dismiss that we also feel insecure”

“It’s regrettable that due to the violent incidents here, and more prosperous development elsewhere, that our grandchildren are moving to live elsewhere. I can’t imagine any of them wanting to live in Pattani, except if they’re kids who don’t study.”

“I don’t view people who just moved in as orang tani (Patani people) since they’re not bound to this place. They’re Buddhists, if they’re Thai. If they’re Chinese then they worship Chao Mae Lim Ko Niew (the local Chinese heroine) so they’re not orang tani.”

“Malays believe in God, so they’re okay with others who do so as well. But I have a feeling that things are changing, and that this common sentiment is being fragmented into groups.”

Who should the word “bandit” be used to describe?

“The word ‘bandit’ means someone who robs, coerces other people with force and threats. Do you think that this word can be used with Malay people? Of course not. There are no bandits, only people who think differently. You [Siam] should ask yourselves, rather, what you did to make them hate you.”

“To solve the problems here, the Thai people have to resolve their issues first, starting with Bangkok politics and then Deep South issues. Then they can implement models to use here. At the moment however, I don’t see when the situation will be resolved.”

“I want everyone to coexist and assimilate peacefully. For example, if Islamic law is implemented, it was to be accepted by the people it will govern. Which situations can it be applied to, and which not? If they don’t consider the needs of the people, then it well revert to a situation not so different from this one.”

“I was taught that living together like this is already good. I haven’t gone so far as to think about how we would live if this area became independent. The question of whether independence is beneficial to us is being answered by a lot of competing voices, but personally I still can’t clearly picture a state of independence. For example, if we were to become independent tomorrow, who would govern this place? What would the governing system be like? I don’t see any democracy from that.”

“Whatever kind of government to be implemented, if the current system of the civil service continues to be implemented here, then there’s no end to the conflict. People in the civil service should change their mindsets when coming to govern here and see themselves as serving the people, not ruling over the people. At the moment, civil servants here have no sincerity, and most of them have no love for the region at all. For example, the Pattani governor only has to serve here for one year. People who get to rule over this region should love it, too.”

“I think that civil servants here should be able to speak Malay in the five years that they are stationed here.”

Translated into English by Asaree Thaitrakulpanich

Related stories: