In Part II of the Modern Thai student Movement paper, we look into how 2 student organizations in Isan, Thailand’s Northeast, began. While one focus on raising political awareness and mobilisation, another choose to focus on grassroots and local issues. Both, however, describe themselves as neither Red or Yellow along the current color-coded political divide.

Nonetheless, it has become clearer that the new military regime’s reform policies and proposed bills on various issues, such as education, energy, natural resources, land reform, forestry, immigration, education and tax, will benefit some groups of people while negatively affecting others. NGOs and political activists have begun to challenge the junta once again despite the imposition of the martial law, which gives the regime unprecedented power to make arrests over any expression of anti-coup opinion. In November, five student activists from the Dao Din group of Khon Kaen University in the Northeast, gave the three-fingered salute to Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha, the junta leader. The students were immediately detained and later interrogated by the military. The military also involved their parents and threatened to have them fired from the university if they did not accept the junta’s conditions. Although the junta might expect the harsh treatment and intimidation of the Khon Kaen students to serve as a lesson to keep other young activists at bay, the result was the opposite.

One after another, despite the presumption that the era of Thai student movement ended with the bloody student massacre of October 1976, student activists of various political orientations began once again to voice opposition to the suppression by the junta. Although these new student movements are not mass youth movements affiliated with political ideologies as in the 1970s, neither are they affiliated with the current colour-coded political divide in Thailand. These young activists began to engage in many regional and national problems despite the obstacle of the martial law. To look into the history, dreams, and aspirations of these student activists, who are now at the forefront of Thailand’s political mobilization, Prachatai introduces the series “The Modern Student Movement,” by Emma Arnold and Apisra Srivanich-Raper.

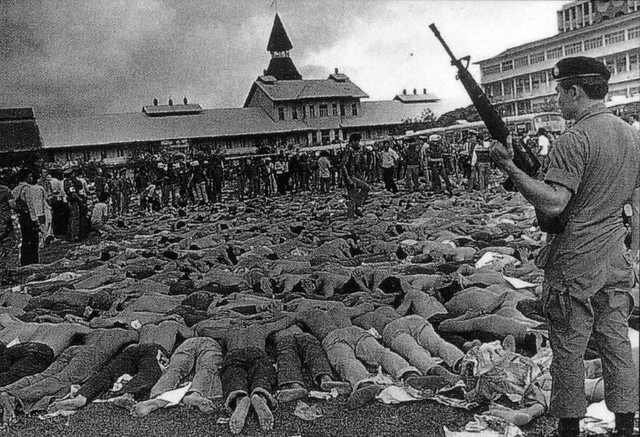

Student forced to lay down facing the ground during the student crackdown in Thammasat University, which later turned into a brutal massacre on 6 October 1976

Continue from Part I

The Politician

Artit Chansi, Political Science Student, Ubon Ratchathani University

Though he is still a student, Artit Chansi is already on the campaign trail. The 22-year-old, who studies political science at Ubon Ratchathani University, frequently travels to nearby villages to talk with community members and learn about their political perspectives.

“I go to villages to share ideas with both Red and Yellow Shirt people, to understand why they have chosen each side,” he said. “If I know about opinions from both sides, from Red Shirts and Yellow Shirts, I can understand their backgrounds.”

Understanding these varying perspectives is key to Mr. Artit’s future career. He plans to become a local politician and to be part of the changing political structure in Thailand.

Despite having come straight from class, Mr. Artit looks like a politician; he is clean cut in a button down shirt and dark jeans. He speaks sincerely, leaning forward and resting his elbows on his knees.

Decentralization, he explains, is key to the future of politics. Working with local people in their communities is the best way to create positive change for society.

“I want to help people around here because each person has different problem,” said Mr. Artit. “I also want to work to fix injustice.”

Mr. Artit is not a member of a politically active student group, but is nonetheless part of the modern student movement. He has chosen to challenge conventional politics through becoming a part of the governmental system.

Mr. Artit believes that Thailand is currently in the process of moving from democracy to advanced democracy, which he vaguely defines as moving outside of the confines of the “old traditional box” of governance.

“In democracy everybody should have participation in the system,” he stated. “It is not only about students who study political science, it is not only our responsibility. It is everyone’s responsibility for society. It is their role as a citizen of the country.”

As a budding politician, Mr. Artit looks forward to fulfilling this obligation.

Grassroots Politics

Dao Din, (ดาวดิน) Khon Kaen University

Affiliation: Independent, Members: 20

Defiant and outspoken, members of the group Dao Din are at the forefront of the modern student movement in Thailand. For them, being politically active is not a choice, it is an obligation.

“Since we are born into this world, we have a responsibility do something for society before we leave,” said Nitikon Khamchu, member of Dao Din and recent graduate of Khon Kaen University.

Dao Din focuses on grassroots work with local communities promoting social justice, human rights, and equality. But in the current situation, grassroots effort are rarely enough.

According to Mr. Nitikon, those who have the power to truly improve society are elected politicians who are on a “higher level”.

Dao Din student activists protesting in March against Constitutional Court's ruling to nullify the general election

The challenge, he explained, is that these “higher level” politicians are not concerned with the needs of the common people. Mr. Nitikon is tall and quiet, but it is clear the younger members of the group respect him greatly. “I believe that the big political parties right now belong only to the investors. Those parties do not belong to the people,” said Mr. Nitikon. He is not the only person to hold these frustrations.

Dissatisfied with the country’s existing parties, a group of activists have established a new political party. Known as the Commoner’s Party of Thailand (CPT), they aim to challenge the conventional top-down approach to politics and to capture the voice of the “common people” of Thailand.

Inspired by his experiences working with Dao Din, Mr. Nitikon became one of the founding members of the Commoner’s Party. He now is a self-described “recruiter” and works with politically active student groups, like Dao Din, to engage the younger generation.

The party’s platform includes challenging lèse-majesté laws, advocating for government decentralization, amending the 2007 constitution, and advancing labor rights. Prominent academics such as Nidhi Eoseewong, a former history professor from Chiang Mai University, have lent their support.

Members of Dao Din support the CPT. Whereas many other student groups shy away from overt political statements, Dao Din members are not afraid of voicing their opinions. They have involved themselves in their country’s messy political situation out a strong desire for change.

“I expect that this party will be the stage for ordinary people to express their opinions,” Mr. Nitigon explained, “because this party does not belong to me or anyone else. This party belongs to the common people.”

Five members of Dao Din group still wearing t-shirts saying in Thai ‘mai ao rat-pra-harn’, meaning ‘No Coup’ while they were on the police pickup-truck after they were arrested for flashing the three-fingered salute, a symbol of political defiance defrived from the 'Hunger Games', in front of Prayut Chan-o-cha, the junta leader, while he was giving a speech at Khon Kaen Provincial Hall on 19 November 2014.

The Commoner’s Party of Thailand represents a new type of political organization—one that works on the policy level to represent the voices of the general population. Taking a grassroots approach to politics is what supporters believe will be the group’s success.

As Thailand is divided between two increasingly polarized groups, there is much talk of civil war as the only solution. Mr. Nitikon sees the Commoner’s Party of Thailand as offering an alternative; “What we have done is create a third area for those who disagree with the civil war; to give them power to do something.” Though his demeanor is calm, his words are full of hope.

The Thai modern student movement to be continue on Part III

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”