Kamthong Somchai started

his day on Jan. 17 as usual. He left a deserted guardhouse, which is his only shelter with his tricycle, to look for recyclable garbage on Lad Phrao road, not far from the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) rally. He was wearing a white t-shirt saying “We love Yingluck; we love Democracy,” which he had received during an election campaign.

Captured by a group of alleged PDRC guards, he was asked if he was a red-shirt supporter, Kamthong told them frankly that he was a red-shirt supporter even though he knew that the answer may lead to negative consequences.

He was tortured and beaten for several hours, and blacked out several times. He was later released. His tricycle, wallet and ID card were taken along with 3000 baht in cash.

Kamthong Somchai under treatment in hospital with a laceration wound on his right eyebrow

Although the red colour led to him being beaten, he still proudly affirms his red identity and his admiration for Thaksin.

“I am red-shirted. I bond with the movement. I joined the red shirts because I love Thaksin. Red shirts love Thaksin because of his practical results.”

Kamthong was one of the red shirts who have actively participated in the red-shirt movement since after the coup d’état, the 2009 demonstrations and the 2010 red-shirt demonstrations till the day of the military crackdown.

Kamthong has worked in various positions in the past twenty years. He once worked as a construction worker in Thailand and abroad, as a security guard and later as a garbage recycler for almost two years.

“Searching for reusable or recyclable stuff is not an ordinary job because I don’t need to invest anything, only my labour. I can sell the stuff for 600-700 baht per day,” he said. “Although it’s trash, to me it’s cash.” He said could earn almost 10,000-20,000 baht each month if he was hard working enough.

He has no relatives in Bangkok. He feels a bit secure because of the universal healthcare scheme, initiated by Thaksin.

Back in his hometown in Nakhon Phanom Province, he used funds from the Village Fund to support his rice farming, a policy also initiated by Thaksin.

“Thaksin is the first politician to really respect Isan people,” he said.

Kamthong is one of the red shirts described as the emerging new middle class/lower middle class in the latest research on Thai politics

Re-examining the Political Landscape of Thailand by Apichat Satitniramai, Yukti Mukdawijitra, and Niti Pawakapan, among others, which tries to understand who the red shirts are, what the red-shirt movement is and the current colour-coded political conflict. The research used surveys, focus groups and interviews and the report was launched in late January.

Apichat is an economist from Thammasat University, Yukti is an anthropologist also from Thammasat and Niti is a political scientist from Chulalongkorn University. The three initiated the project after the 2010 military crackdown on red-shirt protesters as they saw that there was no research giving a satisfactory explanation of the colour-coded political conflict.

According to the study, the socio-economic changes in Thailand over the past 20 years have led to the emergence of a new kind of citizen which the research calls the “new middle class” or lower middle class, or the red-shirts. This group’s characteristics and interests differ from the old middle class or the middle-upper middle classes which constitute the “yellow shirts,” the colour originally adopted by the pro-establishment and anti-Thaksin People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD).

From surveys in 2010, the researchers also found that red shirts were more likely to work in the agricultural or non-formal sectors than yellow shirts. In contrast, it was found that a higher proportion of yellow shirts were civil servants, state enterprise employees, or business people, than among red shirts and neutrals. Moreover, more yellow shirts than red shirts had completed a bachelor’s degree or higher. Thirdly, yellow shirts have higher incomes than red shirts or those supporting neither side.

“In general, yellow shirts are those with a higher economic and social status than red shirts as shown by their higher level of education and more secure employment as civil servants, state enterprise employees, businessmen, and professionals, whereas most red shirts are those with a lower level of education, whose employment has an irregular income like commercial agriculturalists, semi-skilled and skilled labour, self-employed, etc.,” concluded Apichat, adding that the new middle class account about 40 per cent of the population.

The demands, needs and aspirations of the new middle class are different from the old middle class. Former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, during the time of Thai Rak Thai Party, seemed to notice this and intentionally designed policies to transform this new social class into the strong base of his party. Meanwhile, the political reform resulting from the 1997 Constitution had greatly transformed the Thai political landscape. The charter, which focused on decentralization of power and empowered MPs, political parties and local administrative bodies, motivated politicians to respond better to voters’ aspirations and demands through macro-level policies. It also enabled the government to be more effective in driving policies and platforms that had been promised to voters during election campaigns.

Thaksin came at the right time. Unlike other politicians, Thaksin was able to transform his campaign promises into tangible policies, says the research.

“The Thai Rak Thai Party under Thaksin Shinawatra was created at this transition. That made him the first elected prime minister who was able to deliver the promised policies very quickly,” says the research. “This is the first time that the ballots votes of the majority really affected their lives.”

The garbage recycler said in the past he did not care much about general elections as he went to work far away from his registered residence. His mind was changed after the Thaksin era. He cared about elections. And especially after the 2006 coup, he was even more determined to go to vote, no matter how much it cost him to travel back to his hometown or how much he lost from his daily wages.

As the changing political landscape led the new middle class voters to realize their rights as citizens and the power of their votes in affecting their livelihood, the rearrangement of electoral politics reduced the influence of the old middle class who did not seem to care much about their voting rights because they had various tools for negotiating with the government. “Electoral politics at the national and local levels have greatly reduced the influence of the old middle class over the state, simply because they are the minority,” the research notes.

Because the old middle class are the minority, the Democrat Party, popular among the old middle class, has unsurprisingly won no election since 1992. This old middle class party, which regularly joined coalition governments before the political reform, has never had a chance to form a government since, except in 2009-2010 under Democrat leader Abhisit Vejjajiva, in unusual circumstances, the research elaborates.

“If the Democrats could do [what Thaksin did], the red shirts would not hesitate to vote for them, but as you can see, the Democrats have only been interested in the groups who have supported them. It’s not that the red shirts hated the Democrats from the beginning, but because they have never cared for the red shirts and the Isan people,” said the garbage recycler.

The research says the current political conflict in Thailand would actually be normal if there had been no military coup d’état. This conflict may be categorized as distributive politics where groups of people who have their own interests, distinct from other groups. They resort to using electoral politics to push for state policies to serve them. This is a normal conflict which can erupt in any society especially where there has long been high economic disparity, the research says.

However, this conflict escalated because of the military coup d’état which overthrew Thaksin in September 2006. “Because of the coup, the conflict has developed into a conflict over political rules. The red shirts are fighting to protect democratic rule, electoral politics. They want the power holders to be connected and committed to the voters and come from elections and without interference from unconstitutional powers or the invisible hand. Meanwhile, the yellow shirts fight to reduce the power of elected politicians” The PDRC proposal to have an appointed People’s Council to govern and reform the country for 12-18 months is a clear example of such an attempt to reduce the power of politicians.

Even though Kamthong saw the significance of elections, he said he was kind of fed up with them. “We voted and then they took over power -- repeatedly. In no more than two years, they will try to seize power again. We can’t do anything.”

The researchers argue that even though it seems to be a conflict between classes, it does not propose that class -- old or new middle class -- is a determining factor in the colour-coded identities.

Interestingly, because the red shirts are not the poor, this implies that they are materially ready to dedicate their time and resources to join the red-shirt movement. “This in a way explains why the movement has lasted for years -- because red shirts are not that poor,” the research says.

The poorest in the country, according to the survey, cannot be identified with any politically coded colour.

The researchers point out that both red shirts and yellow shirts are pro-democracy. They, however, put different emphases on democratic values.

“The ideologies of the red shirts and yellow shirts are not those of opposing ideas as the media likes to portray it. Both groups value democracy, only they have different emphases,” the research argues. To the yellow shirts, because their smaller population, they call for checks and balances from power outside parliament or appointed power, while the red shirts, because they have more and more power as electoral politics has developed, feel empowered by their voting rights. Therefore the red shirts are more committed to the parliamentary system. The red shirts give priority to parliamentary democracy, elections, and equality. They emphasize equality in accessing political power and justice and participation in politics. That is why they opposed the coup d’état and interference from unconstitutional powers, whether the independent state agencies, the army, or the courts, the research explains.

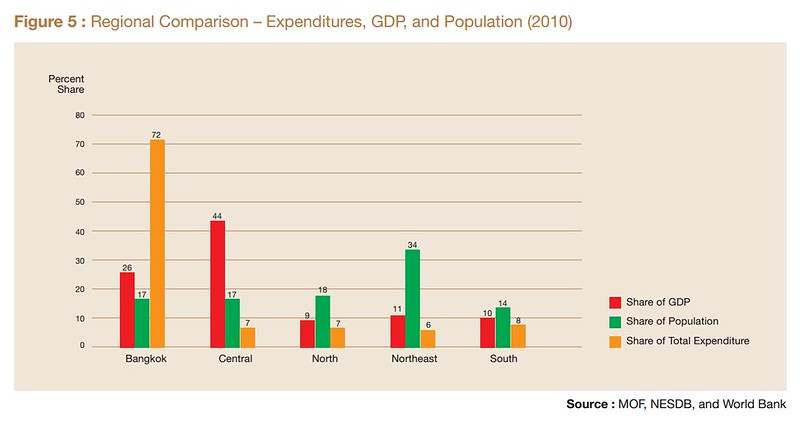

Another way to understand why the yellow shirts are no fans of electoral politics is to examine figures from a

World Bank report.

The World Bank chart shows that even though Bangkok represents only 17 per cent of the population and 26 per cent of GDP, it accounted for about 72 percent of the state expenditures in 2010. In contrast, the Northeast accounts for about 34 per cent of the population, 12 per cent of GDP, but only shared 5.8 per cent of total expenditures in 2010.

The research explains that as Bangkok is the centre of the country, as in the saying “Bangkok is Thailand”, the voting rights of Bangkokians do not mean much to them because all governments need to invest in Bangkok. Unsurprisingly, most yellow-shirt Bangkokians tend to see populism in a negative way. Populist policies are not much benefit to them and divert state resources to support people in rural areas.

The garbage recycler highly praised the populist policies initiated by Thaksin. Asked what he thinks about the yellow shirts’ allegation that populism does not yield sustainable results, Kamthong replied “They’re richer than us. They’re more ready and more secure. They can say anything about populism because they don’t need it.”

Having worked in various low level jobs, he said he is used to the insulting looks of Bangkokians.

“I don’t hate Bangkokians who disdain Isan people. With or without political conflict, they have been looking down on us, but we can live with it. However, after the incident [when he was assaulted], I feel unsafe.”

Niti observed that the sentiment of insulting Isan people because they are of a lower class has been around for several decades and is partly a legacy of the Cold War when the now-defunct Communist Party of Thailand had its base in the Northeast.

“When I talked with Isan people, they always told me that they feel neglected and inferior. The saying that ‘Isan people could only be servants and gas station attendants’ really hurts them,” said Niti.

The original quote is from Charoen Kanthawongs, member of an advisory committee of the Democrat Party, who once

told the New Straits Times that "People in the Northeast are employees of people in Bangkok. My servants are from the Northeast. Gas station attendants in Bangkok are from the Northeast."

Economic disparity is not the only factor that turned most Northeastern people into red shirts. Another important factor, the research says, is the resentment, retaliation and vengefulness from the feeling that they were deprived of their political rights by the 2006 coup, that they have long been treated unfairly by the state, given the unfair distribution of state resources, and that they have been treated as second class citizens for so long. The realization of this injustice and inequality formed the identity of the new cultural citizens who came out to demand their rights in the name of the red-shirt movement.

Red-shirts binding Kamthong’s wrist with red threads. It is a traditional Thai ceremony believed to bring back blessings and luck to the person after a bad incident at the Ko Tee red-shirt rally site in Lak Si, Bangkok.

After days in hospital, Kamthong stayed at a red-shirt rally site in Lak Si, outer Bangkok. He was welcomed with a wrist-binding ceremony by fellow red-shirts who helped take care of him and provided him with food, new clothes and a new mobile phone.

Last week, a “person from far away overseas” gave him a brand new motorized tricycle and 15,000 baht in cash so that he could restart his garbage recycling career.

He said he could not be happier and that he will continue to fight with the red-shirt movement.

Atippat Jeerapatpimon, representative of the Red Comrades group, handed over a motorized tricycle and 15,000 baht in cash to Kamthong. Athipphat said a 'person from far away overseas' sponsored the donation.